Submarine cables: seismic sensors for maritime ports

From digital highways to global sensors. Fiber optic infrastructure beneath seas and oceans can become an unprecedented seismic and environmental surveillance system

The submarine cables supporting 99% of the planet's data traffic—over 1.7 million kilometers of fiber optic according to the United Nations—are transforming into global-scale seismic sensors. This network, equivalent to 42 times around the Earth's equator, can now become an unprecedented surveillance and early warning system for ports and maritime infrastructure vulnerable to earthquakes, tsunamis, and other natural hazards.

- For the port and maritime sector, this new functionality of submarine cables represents a unique opportunity to protect critical infrastructure and strengthen resilience against natural threats. If fiber optic submarine cables consolidate in this field, risk management would enter a new dimension, enabling early warnings that save lives and protect investments worth billions of euros.

Submarine cables: critical infrastructure for ports

Ports increasingly depend on vulnerable submarine installations: power cables for wharf electrification, fuel pipelines, automated mooring systems... Any seismic event, tsunami, or submarine landslide can compromise these infrastructures and paralyze operations for weeks.

Ports located in seismically active zones—many in Asia are situated near the Pacific Ring of Fire—know this threat well. In the March 2011 tsunami in Japan, six major ports (Hachinohe, Sendai, Onahama, Ishinomaki, Kashima, and Hitachinaka) suffered considerable damage. In the Mediterranean, the 1908 tsunami near Mount Etna caused 80,000 deaths, a reminder that this threat also exists in European waters.

The question is: what if the same digital infrastructure connecting ports could also protect them?

From digital highways to global sensors

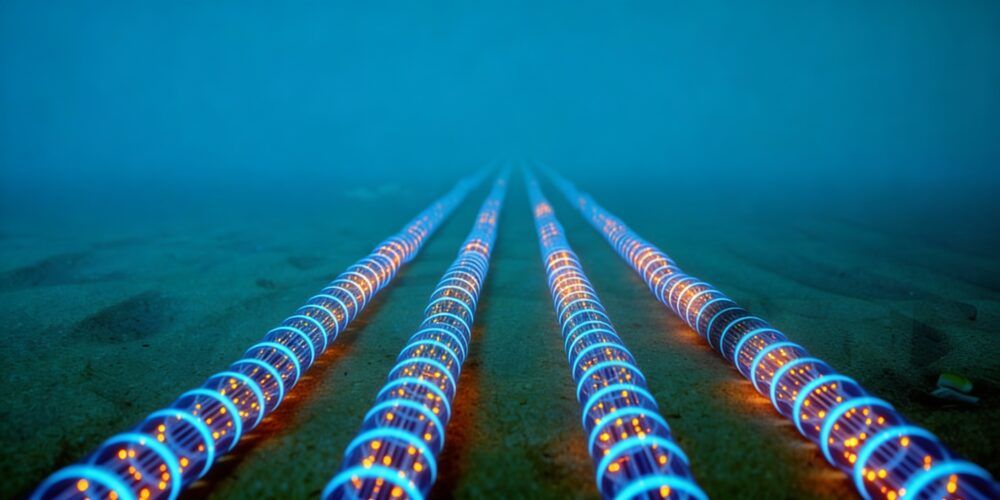

Essentially, submarine telecommunications cables are optical fibers protected by multiple layers of steel, polyethylene, and waterproof materials. These lines are designed to withstand extreme seabed conditions and transmit information through laser light pulses through the glass.

But these cables can also detect any minute change in their underwater environment. How is this possible? Thanks to two physical phenomena that occur naturally in optical fibers:

- Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS)

- Brillouin Optical Time Domain Reflectometry (BOTDR)

Although their names are complex, their operation is based on a relatively simple principle: converting vibrations and temperature changes into optical signals that can be measured, creating a neural network in the seas capable of sensing any disturbance.

How Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) works

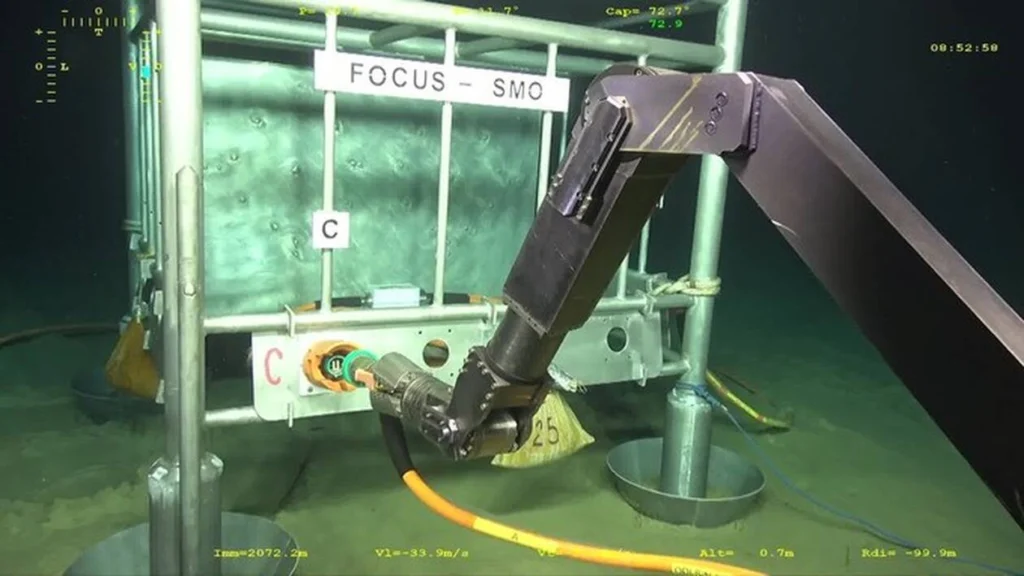

Arantza Ugalde, researcher at the Institute of Marine Sciences-CSIC (ICM-CSIC), explains to PierNext that DAS technology "converts a conventional telecommunications cable into thousands of separate virtual sensors, typically a few meters apart along tens of kilometers of cable."

DAS uses equipment called an interrogator, connected to one end of the optical fiber, which sends laser light pulses along the cable. Part of that light is reflected due to microscopic irregularities in the material and returns to the interrogator. Software can analyze how this reflected signal varies over time, allowing the system to detect extremely small deformations caused by vibrations or acoustic waves. These variations allow identification of seismic events or other movements. Additionally, the time it takes for the light to return allows precise localization of the point on the cable where deformation has occurred.

Translating this into more practical terms, Ugalde adds that "with DAS, seismic waves from earthquakes are recorded and, depending on the environment, signals associated with landslides or volcanic activity; meteorological-oceanic signals related to sea state and, potentially, signals associated with tsunamis."

Furthermore, the CSIC researcher explains other data that can be measured with this technology such as "maritime or terrestrial traffic and industrial activities, as well as signals of biological origin, for example, cetacean vocalizations."

French company Alcatel Submarine Networks (ASN), specialized in fiber optic sensing technologies, has developed commercial solutions that convert conventional cables into distributed sensor networks. In this video, they explain how their DAS systems can monitor critical infrastructure in real time, from pipelines to submarine cables, detecting vibrations, intrusions, and seismic events along tens of kilometers with a single interrogator.

How BOTDR technology works: measuring ocean temperature

While DAS detects vibrations and movements, Brillouin Optical Time Domain Reflectometry (BOTDR) specializes in measuring temperature changes along the entire cable. This technology exploits a physical phenomenon known as Brillouin scattering, which occurs when laser light interacts with molecules in the optical fiber material.

The process works similarly to DAS: an interrogator sends light pulses through the cable, but in this case, the frequency of the reflected light varies according to the temperature of the environment surrounding the fiber. When temperature increases, the fiber molecules vibrate differently, slightly altering the frequency of the bouncing light. By analyzing these frequency changes and the time it takes for the light to return, the system can create a detailed thermal map of the entire cable route.

A revealing example of its potential is found on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, where researchers from the EU's ERC FOCUS project detected a 1.5°C temperature increase that coincided with a coral bleaching event that destroyed 30% of local reefs in two years. Without this continuous monitoring, the phenomenon would have gone unnoticed until the damage was irreversible.

For port infrastructure, this thermal monitoring capability has direct applications: from detecting industrial spills that alter water temperature to monitoring conditions of protected marine species in port operation zones. It also allows identification of anomalous ocean currents that may affect navigation or anchoring operations.

Seismic sensors in submarine cables: real cases

The capability of these systems is not theoretical. A project led by Nokia Bell Labs managed to convert a 4,400-kilometer cable between Hawaii and California into 44,000 seismic stations, separated by just 100 meters. To contextualize this figure: it's like having a seismograph every 100 meters along the entire distance between Madrid and Moscow. The system successfully detected a magnitude 8.8 earthquake in the Kamchatka Peninsula and the subsequent tsunami, demonstrating that this technology can cover transoceanic distances.

In European waters, the ERC FOCUS project installed a monitoring prototype with these cables on the coast near Mount Etna, where it aims to prevent a disaster like the 1908 tsunami that caused 80,000 casualties. This initiative demonstrates that the Mediterranean, although perceived as a relatively calm sea, also requires early warning systems.

For maritime traffic, DAS can track the movement of vessels navigating over the cable zones, offering complementary data to AIS (Automatic Identification System) and radar systems. This is especially useful for detecting unauthorized activity or managing traffic in congested port approaches. In some pilot tests, the system has even identified small vessels that do not emit AIS signals.

Direct applications of submarine seismic sensors in ports

The monitoring capability of DAS to detect earthquakes in real time allows rapid assessment of the risk of structural damage to wharves, cranes, warehouses, and other port facilities. The minutes of advance provided by early detection can make the difference between an orderly evacuation and a catastrophe.

In the specific case of tsunamis, cables can register subtle seabed deformations caused by the passage of a tsunami wave, providing crucial minutes of warning before it reaches the coast. These additional minutes allow activation of emergency protocols, halting loading and unloading operations, and moving vessels away from vulnerable wharves.

Fiber optic cables also help monitor other critical submarine infrastructure. DAS technology can detect anomalous submarine currents, landslides, or even ship anchors threatening installations such as power cables for wharf electrification or fuel pipelines. In ports that are electrifying their operations to reduce emissions, this additional protection becomes especially relevant.

Beyond structural safety, bioacoustic monitoring through DAS allows reduction of collision risks with cetaceans in areas of intense maritime traffic, a growing concern in European ports with increasingly strict environmental regulations.

How will fiber optic monitoring networks evolve?

Despite its enormous potential, widespread implementation of this technology faces significant obstacles. The main one is cable access. Most submarine infrastructure is in the hands of large technology corporations such as Google, Meta, Amazon, and Microsoft, which have invested massively in their own cables to connect their global data centers.

- Cable operators fear that sensing technology might interfere with data traffic or occupy transmission capacity. Although original interrogators operated at the same wavelengths as telecommunications, the new generation of devices functions in different optical bands, eliminating the risk of interference.

Nevertheless, Arantza Ugalde is optimistic about the evolution of these technologies in the next decade: "there are more and more fiber cables and it is reasonable to expect a consolidation of their use for sensing, without interfering with communications, based on collaboration frameworks and policies that facilitate access for public purposes."

Another challenge is the range limitation of interrogators. Currently, DAS records data at a maximum distance of 150 kilometers and BOTDR at 70 kilometers. This restricts monitoring to the first section of cable near the coast, before the first signal repeater. In the aforementioned Nokia Bell Labs project, a "loop-back" function of the repeaters is exploited to amplify reflected signals, allowing monitoring of complete transoceanic cables, but this solution is not yet widely available.

Of course, these cables with lengths of hundreds of kilometers generate a large volume of data whose management is another challenge for implementing these measurement systems. For example, a 50-100 kilometer cable generates approximately one terabyte of data per day due to DAS's high resolution.

In the realm of future advantages, Ugalde affirms that "through operational bioacoustic monitoring in maritime traffic zones, the risk of collisions with cetaceans can be reduced." The CSIC expert finally concludes that "AI will be central to managing the large volume of data, and the real change will come when these capabilities move from pilot projects to stable services integrated into global observation and risk management systems."

While pilot projects demonstrate technical viability, the next phase requires public-private collaboration frameworks that facilitate access to existing cables without compromising telecommunications operations. Ports that early integrate these monitoring capabilities into their resilience plans will be better positioned to protect multimillion investments in electrification, automation, and sustainability infrastructure.

The question is no longer whether submarine cables can become port protection systems, but how long ports will take to incorporate this technology into their risk management strategies. In a context of growing climate and seismic vulnerability, waiting may be more costly than acting.