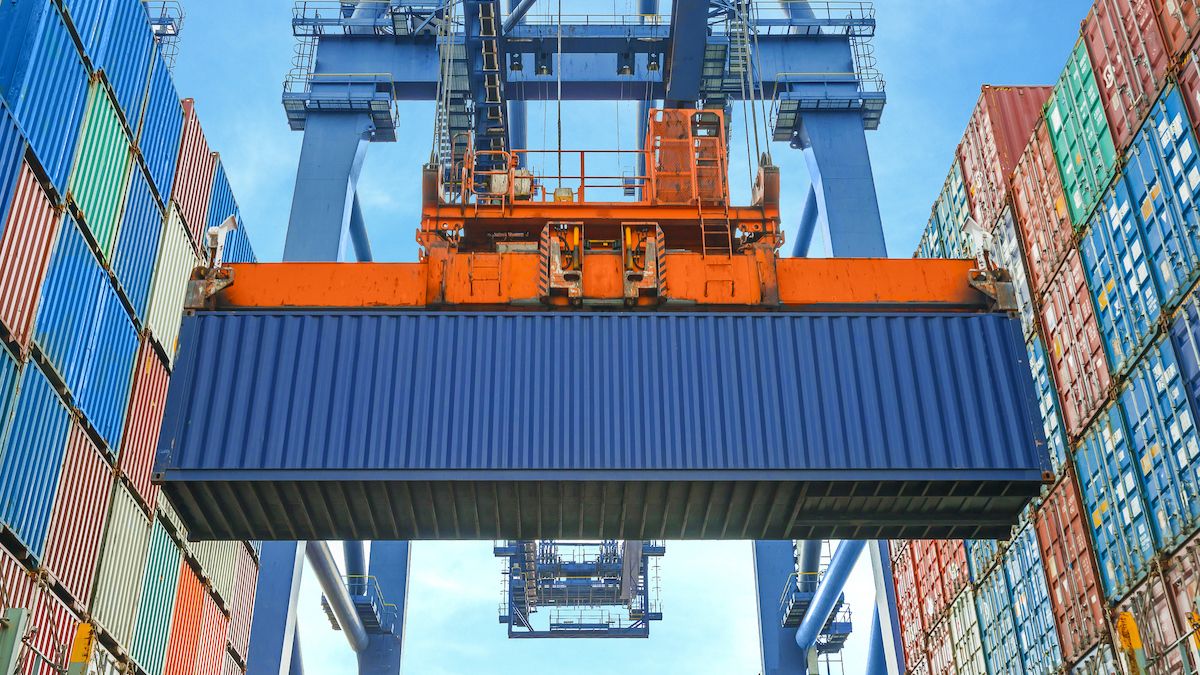

Even though economic recovery and an associated boost to maritime shipping are to be expected, the pattern will not be even across the world. (Gettyimages)

Even though economic recovery and an associated boost to maritime shipping are to be expected, the pattern will not be even across the world. (Gettyimages)

Will maritime transport grow in Europe?

The world is speeding up and the way we consume is changing: the circular economy, servitization, buying local, etc. And all this is affecting supply chains. That is why port operators are scrutinising current trends to see what the future might hold.

Carles Rúa is the Chief Innovation Officer at the Port de Barcelona and Director of the Master’s degree in Executive in Supply Chain Management at the UPC.

Even though economic recovery and an associated boost to maritime shipping are to be expected, the pattern will not be even across the world. (Gettyimages)

Even though economic recovery and an associated boost to maritime shipping are to be expected, the pattern will not be even across the world. (Gettyimages)

There is a strong correlation between the growth of international trade and patterns of global GDP. According to the World Trade Organisation, over the last few decades international trade has multiplied global wealth (GDP) by a factor of 1.5. This phenomenon peaked in the 1990s with an average multiplier of 2.4. In recent years, however, the figure has settled round a value of 1, and it has dipped below 1 on occasion since 2016. All this clearly suggests that globalisation is slowing down.

Despite the negative impact of COVID-19 on the world economy, most experts agree that global GDP will grow in coming decades. This is due in part to a growing global population, that according to the United Nations will reach 10 billion people by 2050 and can be expected to stabilise at around 11 billion from 2100. As a result, global trade should also grow, but that reduced multiplier will likely mean it does so at a slower rate than in the past.

The increase in the population – 2.5 billion by 2050 – will not be spread evenly across the world. It will be concentrated in Africa and Southeast Asia, whilst Europe may lose up to 5% of its population, an example of what will happen in more industrialised countries.

In the face of this scenario, what are the most important factors that might affect maritime shipping in the world in general and in Europe in particular?

- Energy Transition

According to Future Maritime Trade Flows, a report by the International Maritime Forum, the percentage of energy commodities transported by sea fell from 60% in 1970 to 30% in 2017. Globally, the absolute value of energy commodities shipped, mainly coal and oil, is expected to continue to grow until 2030. But it will likely decline from then on as a result of measures to combat climate change bring about the transition towards renewable energy. The peak could come earlier in the more developed parts of the world, which tend also to be the most demanding in terms of environmental protection.

The decline of the oil industry and the consequent loss of refineries, particularly in Europe, could also lead to slowdowns in related industries, principally the base chemicals industry. It could also negatively affect a key player in many ports, heavy industry, which is sensitive to the cost of energy and might move to countries with cheaper energy or where CO2 emissions are less strongly regulated.

- The Circular Economy

The rise of circular economy will affect the movement of many cargos, particularly minerals such as iron and bauxite, the principal aluminium ore. Minerals are a significant fraction of global maritime shipping and their decline will negatively affect international trade in solid bulk cargos.

In Europe, aluminium recycling in the automotive and construction industries is currently running above 90% and above 75% in the drinks industry, which means that up to 50% of demand for aluminium could be met from post-consumption recycling by 2050.

- Regionalisation of Trade

The rise of the circular economy and other factors at play could lead to greater regionalisation of trade. The trend towards local consumption is changing supply chains. In some cases, centres of production are being relocated nearer to the point of consumption. There are several reasons for this: the demand for more personalised end products, the need to shorten time to market, and the decreasing importance of labour costs.

In business terms, this will lead to higher intra-regional flows at the expense of intercontinental routes and increased short-sea shipping to the detriment of deep-sea shipping.

The trend towards local consumption is changing supply chains. In some cases, centres of production are being relocated nearer to the point of consumption

- The Development of e-Commerce

E-commerce is playing an ever more important role in people’s consumption habits, a trend that has accelerated lately due to COVID-19 lockdowns. But e-commerce requires a degree of responsiveness that is hard to deliver through maritime shipping, so that some trade is being diverted to faster, more flexible modes of shipping.

- Changes in the Automotive Industry

The future of the global automotive market is going to be rather uneven. With 840 vehicles per 1,000 inhabitants in the United States and 602 in Europe, opportunities for growth there are limited. However, in countries like China, with about 200, or in Africa with less than 50, there is plenty of room to advance.

The transition towards electric vehicles will also lead to significant changes to supply chains. European firms have started to move into the electric vehicle market, but they are behind China, calling into question the future viability of parts of the European industry. On the other hand, an electric engine has approximately 80% fewer parts than an internal combustion engine, which means the need to ship parts, including replacement parts, will decline.

And we must also remember emerging trends in micro-mobility, such as electric scooters and the use of shared vehicles. Taken together with the stalling of the growth of the population in Europe, those trends could lead to lower domestic demand. And if business looks to compensate for that drop through increased exports, it is not clear that European manufacturers will be able to compete in emerging markets as effectively as their Chinese and Indian counterparts who have the advantage of lower production costs.

- The Servitization of the Economy

De-materialisation is already a reality in advanced economies. Services such as Spotify have eliminated the need for physical media such as CDs to be able to listen to music. Netflix and other similar services have killed off demand for DVDs. And those vehicle sharing platforms are a threat to sales of new cars and motorbikes to younger consumers. All this ultimately implies the movement of less cargo, particularly into the most developed economies.

Does all this mean maritime shipping is in danger?

No, of course not. Experts agree that maritime shipping will grow. More slowly than it has up to now, admittedly, but it will still grow. Some maritime shipping sectors are expected to grow significantly, for example shipping for the food industry. More cereals, feed and fodder are likely to be shipped in the future.

At the same time, and despite the negative impact of COVID-19, the leisure-related port sector is expected to grow over the medium to long term. Given the ageing of the population, particularly in Europe, and growing disposable incomes in developing countries, cruises and sea-based activities can only increase.

There is however a real danger that this activity might not be enough to balance out other changes in the developed economies, where stalled population growth and possible decreasing importance to the global economy could lead to lower levels of activity in ports.

Issues, adapting and innovating

In summary, even though economic recovery and an associated boost to maritime shipping are to be expected, the pattern will not be even across the world. In Europe, some trades previously thought to be essential to volumes through ports are expected to grow slowly or even shrink over the medium to long term: petroleum products, coal, raw materials, cars and even some container traffic. Locations highly dependent on that shipping may see sharply lower activity.

These changes are giving ports and industry players cause for thought, since they are going to have to take investment decisions on the basis of alternative futures rather than the extrapolation of existing traffic volumes. They will have to adapt their facilities to the more than likely new needs of the hinterland economy, taking account of possible reductions in some areas.

To address this uncertainty, ports such as Rotterdam, Hamburg and Barcelona are refocusing their long-term strategies to prioritise the response to the future landscape and to redefine the use of their territory in line with those new needs. They are innovating and changing. As has happened since the dawn of history, when the first European cargos were shipped across the Mediterranean, the Baltic and the North Sea.