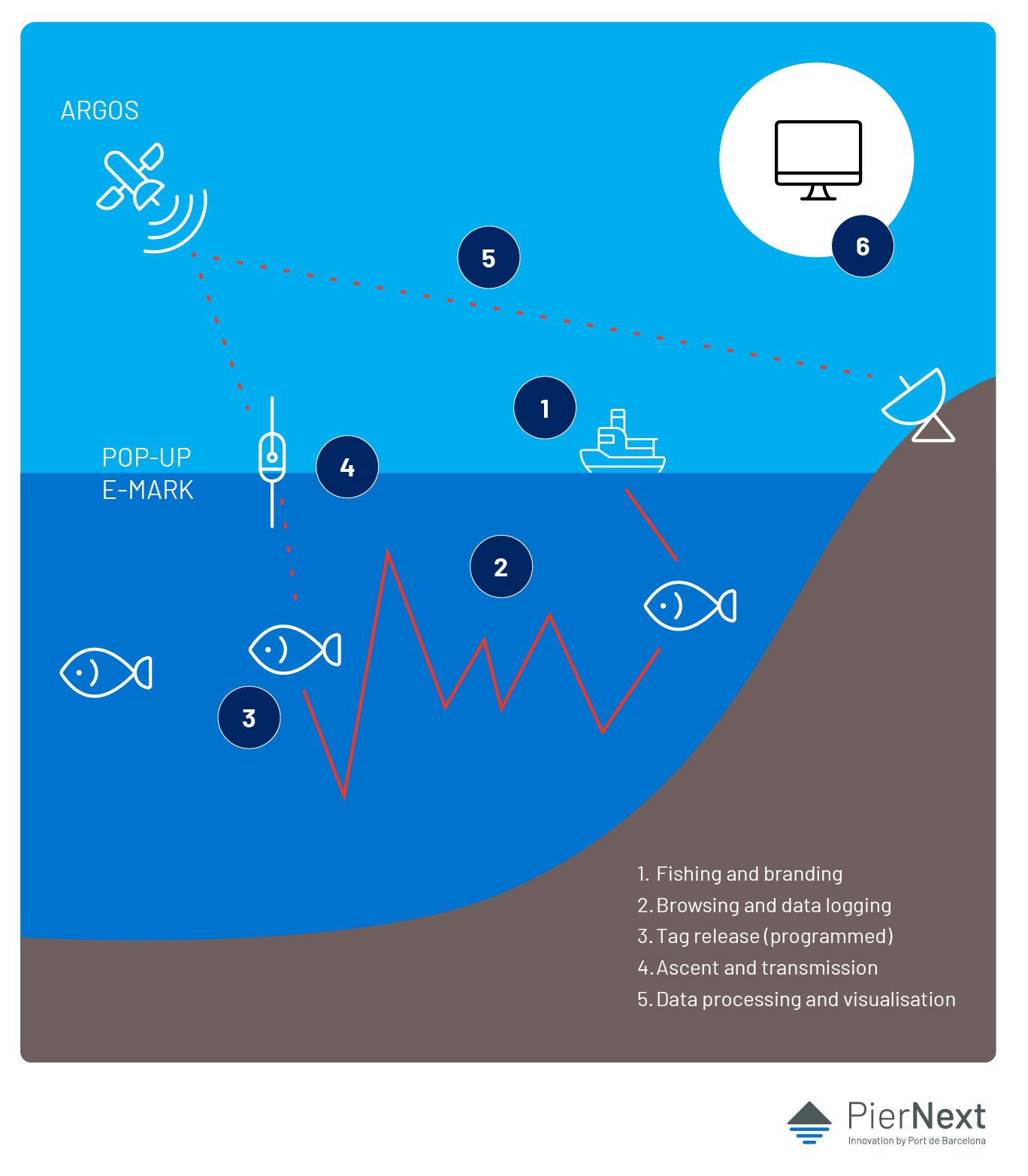

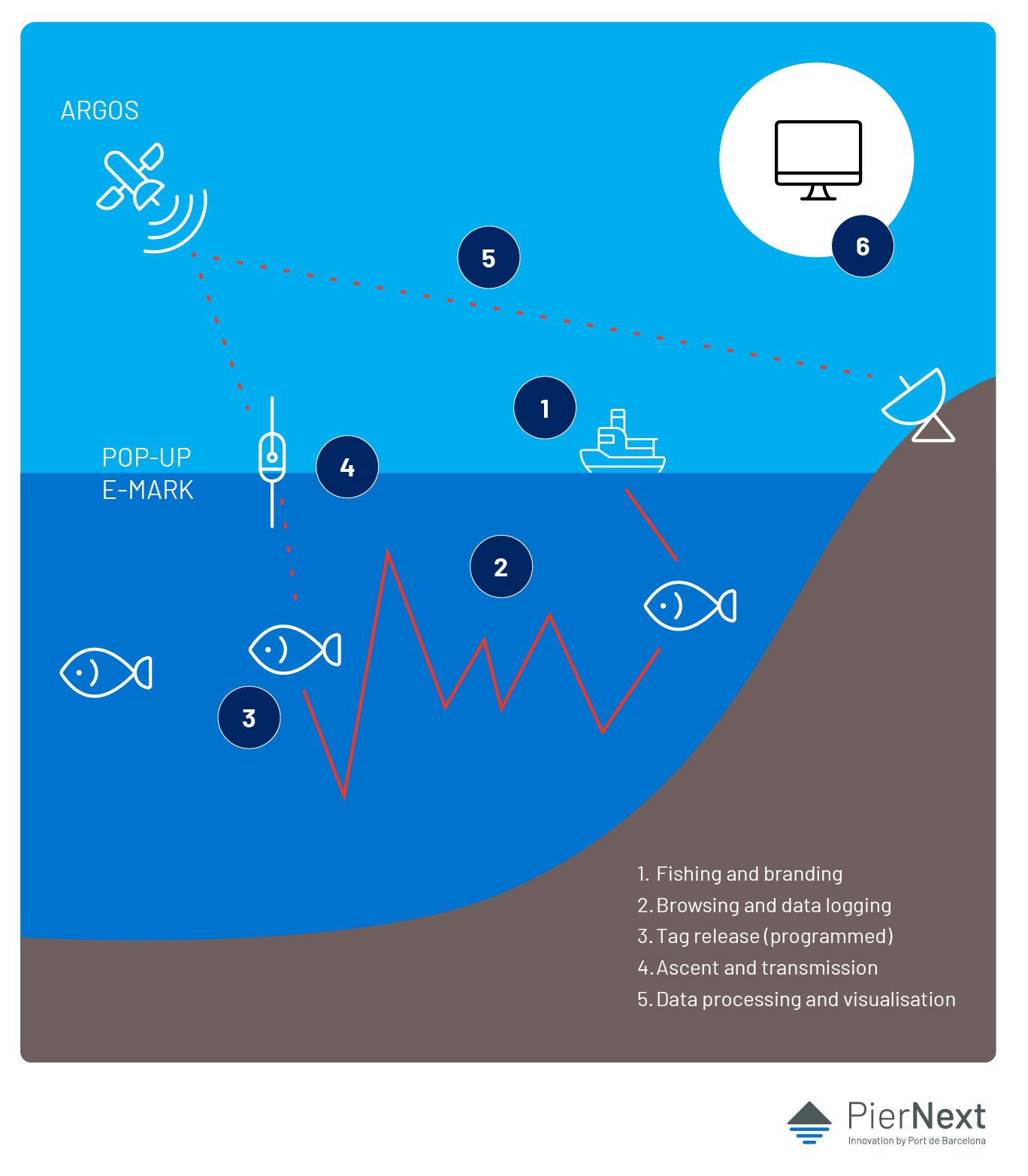

In the bluefin tuna tagging project in the Mediterranean, recreational fishermen are in charge of catching the tuna specified by the scientists. Once they have the fish, the scientists sample them, implant a pop-up electronic tag and then release the fish.

These tags record temperature, light and depth data and are programmed to be released in about a year. Once they surface, they broadcast some of the recorded information to the Argos satellite system. Later, when scientists retrieve the devices, they can access the full data.

"With this data, scientists can see not only the places where the fish have passed, but also the depth, water temperature and other parameters that they then relate to other information to learn more and more about these animals," says Valls.

"Some people ask us what each tag is for. We always reply that each tag serves to fill a knowledge gap. What the information is used for depends a lot on the scientist's objective and what he or she relates the data to. When you consider that not only tuna are tagged, but also sharks, cetaceans and other fish species, it's easy to imagine that there is no limit to what you can learn," says the co-founder of the Scientific Angler Tagging Tour.

Tagging and remote data acquisition by POP-UP electronic tags (basic operation)

Citizen science around ports

Citizen science can be used to gather knowledge and information on a multitude of issues, including those that challenge the oceans: plastic pollution, rising water temperatures, the presence of invasive species or the decline of certain species populations, for example.

As these projects involve the public, most of them are carried out on the coast. And in this context, ports are gaining importance as links between land and sea: in recent years, different citizen science projects have taken shape around ports.

In Sydney (Australia), for example, the Wild Sydney Harbour initiative invites people to report sightings of wild animals (such as penguins, sharks, dolphins or whales) around the harbour via social networks or forms available on the project website. Citizen collaboration allows us to know where these animals are and also how they are affected by interactions with people and boats in a space as busy as Sydney Harbour.

On the other side of the world, the port of Falmouth (UK) collaborates with the international society SeaKeepers to encourage cooperation between recreational boat owners, scientists and environmental researchers to gather information on the state of the water or the seabed. This allows different research groups to understand the implications of climate change or pollution in the sea, among other things.

In these cases (and in the many others that complete the list), these research projects also seek to disseminate, educate and raise awareness, as well as to involve the population in all aspects related to marine life. Scientific Angler tagging days, for example, are always accompanied by lectures, outreach events or plastic collection or monitoring activities.

"A very curious thing happens: people don't associate the sea with nature and wildlife. It seems that wildlife is in the jungles and nature is in the bush," says Valls. "But the sea is nature. The sea is wildlife. And often where people are closest to wildlife is in the sea. We also try to raise awareness about all this," says the co-founder of Scientific Angler Tagging Tour.

Projects that involve citizens generate new knowledge or help to understand different aspects of our environment. (FP)

Projects that involve citizens generate new knowledge or help to understand different aspects of our environment. (FP)

Projects that involve citizens generate new knowledge or help to understand different aspects of our environment. (FP)

Projects that involve citizens generate new knowledge or help to understand different aspects of our environment. (FP)