In China, the world's largest producer of macroalgae, 99% of the algae produced comes from algae farming. (Getty Images)

In China, the world's largest producer of macroalgae, 99% of the algae produced comes from algae farming. (Getty Images)

Seaweed farming: when blue economy turns green

The farming of algae for various purposes is one of the major challenges of the blue economy in Europe. Algae are a low-fat food, rich in fibre, micronutrients and low in calories. In addition, they reduce the acidification of the seas and can be the basis for solid fuels. This is a potential business that the European Union estimates at 9,000 million euros.

In China, the world's largest producer of macroalgae, 99% of the algae produced comes from algae farming. (Getty Images)

In China, the world's largest producer of macroalgae, 99% of the algae produced comes from algae farming. (Getty Images)

Superalgae: superfood, cosmetics, green energy... and much more

When people talk about seaweed farming, they tend to start by saying that it is a superfood, with direct health benefits: low in fat, rich in dietary fibre, micronutrients and low in calories.

But they are also valuable for other uses, thanks to their by-products such as lipids, carrageenan, carotenoids, alginate and algal proteins, as a basis for pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. Even for wastewater treatment and energy production.

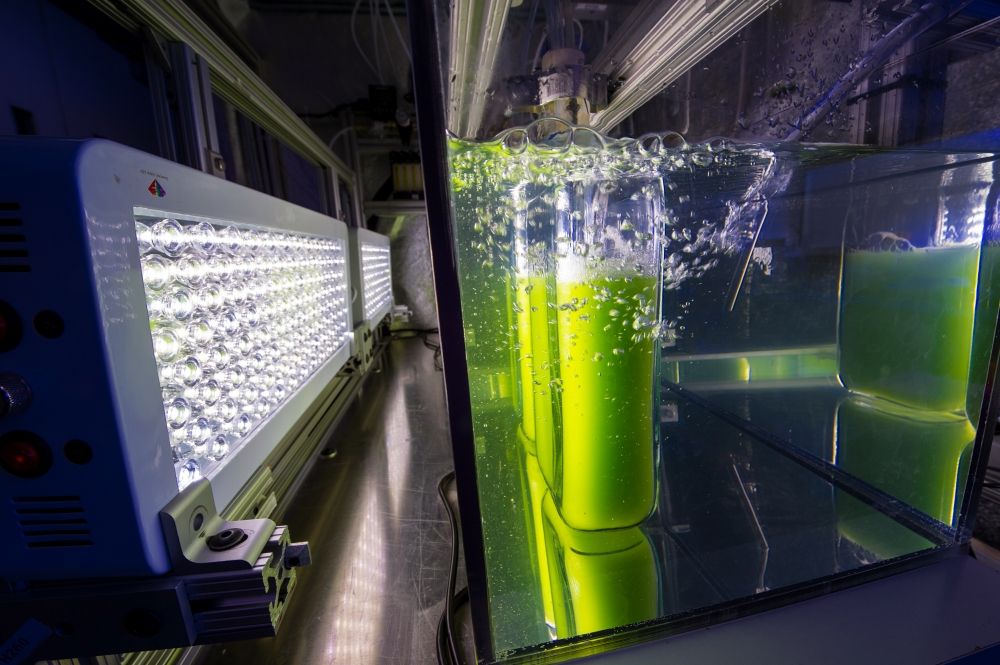

An example highlighted by the European Commission: algal biomass serves as an alternative to fossil fuel-based feedstocks and algal lipids are used for biofuel production.

However, despite its innumerable nutritional values and various commercial applications, it remains an untapped resource in Europe today, although many institutions are promoting algae cultivation and demand is beginning to be strong. In fact, according to the European Union, the algae farming business is expected to reach 9 billion euros by 2030.

Growing seaweed, not harvesting it

Asian countries such as China and the Philippines have always had a very high use of this resource. Europe, on the other hand, has never developed seaweed cultivation to the same extent. In countries such as Ireland, algae were even used in times of famine, but this was not taken a step further.

In China, the world's largest producer of macroalgae, 99% of the seaweed produced comes from seaweed farming. In Europe, 97% is not from algae farming, but from direct harvesting.

According to Jorge Santamaría, co-director of R&D at the Barcelona-based company Algabrava, and co-founder with Raül González, this situation will end up affecting the environment. "Europe has problems coping with the demand for macroalgae and, for this reason, it is resorting to Asian exports," he complains.

For him, this will make Europe dependent on other countries and the algae it works with will not be of such high quality. It is clear, he says, that if the European continent wants to position itself as a reference in this sector, it has to "cultivate and not harvest."

Jorge Santamaría (left) and Raül González, co-founders of Algabrava.

A production of 35 million tons of algae worldwide

From the 1950s until now, seaweed production worldwide has skyrocketed and has grown to 35 million tonnes today.

In the European Union, the algae market is still in its early stages. The 287,386 tonnes of seaweed produced - 99.88% of which was macroalgae - accounted for only 1% of global production. But for Jorge Santamaría, from Algabrava, based in Barcelona, these figures are just the beginning, because he assures that "the cultivation of macroalgae could be one of the great pillars of the blue economy based on sustainability".

No wonder. Macroalgae cultivation has a great benefit in that "it has no impact on the environment,"quite the contrary.

Algae transform CO2 into oxygen and, Santamaría adds, "produce biomass from the sun's energy." He also reminds us that, if they are cultivated in the sea, no irrigation is required, nor is it necessary to destroy habitats or modify land to make them grow.

And yet, at the end of 2019, the scenario was not at all promising. The European Commission's Blue Bioeconomy Forum published Roadmap for the blue bioeconomy, after consulting stakeholders. The roadmap concluded that the development of algae farming has been hampered by factors such as high production costs, small scale of production, limited market knowledge, consumer needs and environmental impacts of algae farming, as well as a fragmented governance framework.

But since this roadmap, a bit of a heavy blow, the Commission has launched and supported several initiatives related to seaweed. For example, it has created the European Algae Stakeholder Forum (EU4Algae) as a unique space for collaboration between European algae stakeholders, collaboration between European algae stakeholders and a one-stop information centre on funding calls, projects and information.

A $17 billion global market

The global algae products market grew from USD 12.12bn in 2022 to USD 13.19bn in 2023, and the market for algae products is expected to grow to USD 17.89bn by 2027, according to a recent study.

The development of alternative protein sources, such as microalgae, is a key trend gaining popularity in the algae-based products market.

For example, Unilever partnered with Algenuity, a UK-based company that develops innovative microalgae-based products for Unilever's portfolio of plant-based products. Algenuity works with the R&D team of Unilever's Foods and Refreshment (F&R) division to explore different microalgae foods.

In the same vein, Aliga Microalgae, a microalgae production and food technology company based in Denmark, acquired Dutch microalgae production specialist Duplaco BV to increase the amount of Chlorella algae products it can produce for the dietary supplement and food additive markets.

Although it is an emerging sector of the bioeconomy, the production of algae in the EU only accounts for little more than 1% of the 35 million tons produced worldwide.

No seaweed, no seas?

In addition to the benefits of algae for human health, their qualities make them indispensable for the future of the seas... and therefore very relevant for those working in the sector.

Algae remove nutrients from aquatic ecosystems, which leads to a significant reduction in eutrophication, i.e. the most notable pollution process in the waters. And, of course, its consequences: uncontrolled proliferation of organisms and plants, interruption of oxygen production, loss of water quality or the appearance of certain toxins.

Moreover, as the European Commission's report Towards a strong and sustainable EU seaweed sector points out, seaweed - when grown in the sea - removes carbon and thus reduces ocean acidification. Or put another way, they prevent seawater from becoming acidic due to excess carbon dioxide.

Growing algae in the sea...and on land

Since 2019, Algabrava has been promoting the cultivation of algae in the Mediterranean, thanks to research and innovation in macroalgae, cultivation in the open sea and also on land. Algae, says co-founder Jorge Santamaría, are more important than we think. "They are responsible for creating 50% of the world's oxygen production. In other words, for every two breaths we take, one is thanks to algae," he explains.

For this company, the future of the sea lies in identifying the species that it shelters and in highlighting those that could be of greatest commercial interest. Here, scientific research plays a key role and is decisive for the sustainability of the oceans. "The founders of the company are marine biologists and we attach great importance to the scientific method," he says.

This is how algae applications are researched in Barcelona

What is the day-to-day research and cultivation of algae like at Algabrava? "We see which species have potential for, for example, cosmetics," explains Santamaría, "and then we analyse the composition of that algae and see what capacity it has. In other words, the first step is to identify the species, but always acting under the umbrella of sustainability.

"Therefore, to alleviate direct harvesting from the sea, we take a very small amount of each species and, in our facilities, we work with that biomass." This way of operating allows them to close the algae's life cycle and have "absolute control, as well as producing it whenever we want without depleting the sea's natural resources."

In other words, Algabrava's facilities are home to various "seedbeds", where its experts cultivate different species of algae. Of particular note is the ulva lactuca, also known as sea lettuce, which is green, edible and found in coastal waters all over the world.

But there are also rara avis such as codium vermilara, or barnacle seaweed, which is gaining many followers in haute cuisine due to its peculiar flavour.

Since many species have limitations for cultivation in the Mediterranean, they explain, they have developed these indoor cultures with which they can control all the physical and chemical factors and maximise the growth of the species.

Macroalgae or microalgae

The development of alternative protein sources, such as macroalgae or microalgae, is a key trend that is gaining popularity in the market and is positioned as a crucial link in achieving the necessary transformation towards a more equitable and resilient food system.

The difference between the two types is size, but Algabrava believes that macroalgae have more potential to be discovered.

It is therefore not surprising that the Commission has been pushing for years with various initiatives to fully exploit the potential of algae in Europe, both in business and social environments. Not only for healthier diets, but also to reduce CO2 emissions and fight water pollution.

Some of the key initiatives proposed by Europe include:

- facilitate access to marine space, identify optimal sites for seaweed cultivation and include seaweed farming and multiple uses of the sea in maritime management plans;

- together with the European Committee for Standardisation (CEN), develop standards for seaweed ingredients and contaminants, as well as for seaweed biofuels

- assess the market potential, efficiency and safety of algae-based materials when used in fertiliser products

- examine the algae market and propose mechanisms to stimulate it to support technology transfer from research to market

- finance pilot projects for retraining and support to SMEs and innovative projects in the algae sector

- studies and discussions to gain a better understanding of, for example, the climate change mitigation opportunities offered by algae and their role as blue carbon sinks, and to define maximum levels of pollutants and iodine in algae

- support, through Horizon Europe and other EU research programmes, the development of new and improved algae processing systems, new production methods and algae farming systems;

A stronger European algae sector would support the objectives of the European Green Deal and the Farm to Fork Strategy, argues the European Commission, as it signals the move towards more sustainable food systems and a more circular economy.

Ultimately, algae have a wide variety of commercial applications, such as food, animal and fish feed, pharmaceuticals, organic packaging and biofuels. Microalgae farming can help regenerate the ocean and seas by removing nutrients that cause eutrophication.

It has a low carbon and environmental footprint and a promising potential for carbon sequestration. Microalgae production can also take place on land and away from the sea, as reflected in the Algabrava case. They are a source of carbon compounds and have applications in wastewater treatment and atmospheric CO2 mitigation.

European institutions know it. Researchers know it. All that remains is for the various actors in the blue economy and, with them, society as a whole, to be aware of it.

TO FIND OUT MORE:

-

- EU4Algae Forum

- European Commission report: Towards a strong and sustainable EU seaweed sector.

- Roadmap for the blue economy

- Farm to Fork strategy

- European Green Deal