One of the new routes runs through the waters of Greenland. [Image by Alexandra Rose]

One of the new routes runs through the waters of Greenland. [Image by Alexandra Rose]

New Arctic routes: breaking the ice of North Pole shipping

The melting of ice in Arctic waters due to climate change has opened them up to ships for long stretches of the year. Estimates say they will be navigable two months a year by 2030 and, one decade later, ships will have 150 days of sailable waters. This new sea trade route would shorten travel time between main ports in Asia and northern Europe.

Jordi Torrent is the Strategy Manager at Port de Barcelona.

One of the new routes runs through the waters of Greenland. [Image by Alexandra Rose]

One of the new routes runs through the waters of Greenland. [Image by Alexandra Rose]

On 16 August 2017, the LNG tanker Christophe de Margerie owned by Russian shipping line Sovcomflot completed the journey between Norway and South Korea along Russia's northern coast. It was the first time a ship of this sort had traversed these waters without icebreakers, and it did so in record time: 19 days, 30% faster than the traditional route through the Suez Canal.

This milestone was only possible because of the warming of the waters in this region, which have seen an average temperature increase of 2.5° C in recent decades. If this trend continues, the Arctic will be navigable for two months of the year by 2030 and increasing to nearly three months by 2040.

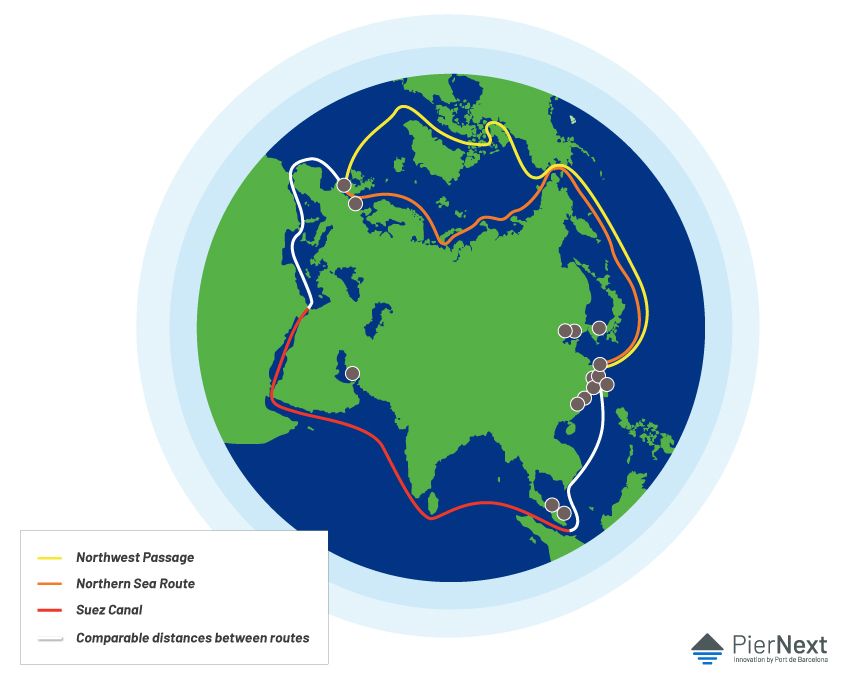

If we analyse ship traffic in the Arctic, there are two main routes: the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route. The first is an old dream of sailors, as illustrious explorers of the 18th and 19th centuries (Alejandro Malaspina, James Cook, John Franklin, etc.) searched for this passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through northern Canada. The second, which mainly crosses Russian waters, has been of less interest historically but will be the first to be ice-free due to climate conditions.

THE NEW ROUTES OF THE ARTIC

It is important to note the different types of ship travel in Arctic waters. Firstly, there is intra-Arctic traffic, which Russian companies have a monopoly on, transporting goods from the mines in Siberia (which produce strategic materials like uranium, tin and palladium) to ports in the region, including Murmansk and Dudinka. A second type are the routes to places in the Arctic for tourism, science or in search of petroleum reservoirs.

But it is the third type of Arctic sailing that could redefine international trade routes, as it involves journeys traversing these waters en route to other leading ports on the global sea traffic scene.

The Arctic will be navigable for two months of the year by 2030 and increasing to nearly three months by 2040.

There is significant consensus that, of the two routes (the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route), the latter will be more interesting, as it will be fully navigable within 10 to 15 years. It will also give Russia more navigable coastline than any other country in the world.

The route through northern Alaska and Canada, however, will be blocked by ice for much longer and involves other difficulties. Researchers at the think-tank The Arctic Institute don't believe it will be viable because the waters won't be freed of ice as quickly as the Russian route (where Siberian rivers make the coastal waters more temperate) and there are numerous islands that allow ice to form more easily on the Northern Sea Route. Plus, this route doesn't have any ports that are deep enough for large vessels.

One of the noteworthy strengths of both routes is the shorter distance between Asian and European ports. For example, a cargo ship going from Shanghai to Rotterdam would have to travel 10,500 nautical miles using the Suez Canal route; via the Northern Sea Route, on the other hand, it would only be 8,500 miles or 8,700 on the route through northern Canada. This reduction in the distances would translate into shorter voyage time, taking up to a week less.

This shortening of the routes, however, only applies between ports in northern Asia (notably Shanghai, Qingdao, Busan and Yokohama) and those north of the English Channel (such as Rotterdam, Hamburg and Antwerp). For Mediterranean ports, like Barcelona, Valencia, Genoa and Trieste, there won't be any big changes, as the routes they ply won't really be affected by increased travel in the Arctic.

But beyond travelling a shorter distance and saving time, it is also important to take into account certain other factors that, today, are a burden on the profitability of the Arctic routes. Climate conditions in this area are very hostile for ships and the goods they transport (very low temperatures, very strong winds), which makes travel insurance more expensive and requires ships to be made of more expensive materials so they won't suffer the effects of these low temperatures. The increased cost of a transarctic sea journey could make it less attractive from an economic standpoint.

![The port of Shanghai is one of the most important in the world and will benefit from the new arctic routes. [Image of REUTERS / Aly Song / File Photo]](https://piernext.portdebarcelona.cat/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/REUTERSAly-SongFile-Photo-1.jpg)

Nor can we forget the technical and technological hurdles. For example, there are fewer navigation aids in these waters and, on the same note, satellite guidance systems also have significant problems in this region. This is due, firstly, to the fact that they need support bases on land, which aren't available in the territories around the Arctic Circle. And, secondly, guidance systems like GPS work with satellites that have a maximum orbital inclination of 55° and struggle in latitudes above 70° or 75°, which makes it difficult to sail in these regions where cartography may not always be 100% reliable.

Finally, we can't forget the political factors. The Arctic is drawing attention from the main powers on the plant, looking to exercise their claims. In addition to the Russian interest in developing the Northern Sea Route, Moscow also wants to exploit the significant petroleum reservoirs in its exclusive economic area. In the Northwest Passage, Canada maintains the route runs through its internal waters, while other powers (like the United States and China) want a greater degree of freedom for vessels under the right to innocent passage. Furthermore, in the case of Beijing, the Arctic routes are an excellent alternative to using the Strait of Malacca, which China considers a vulnerable point in their shipping routes.