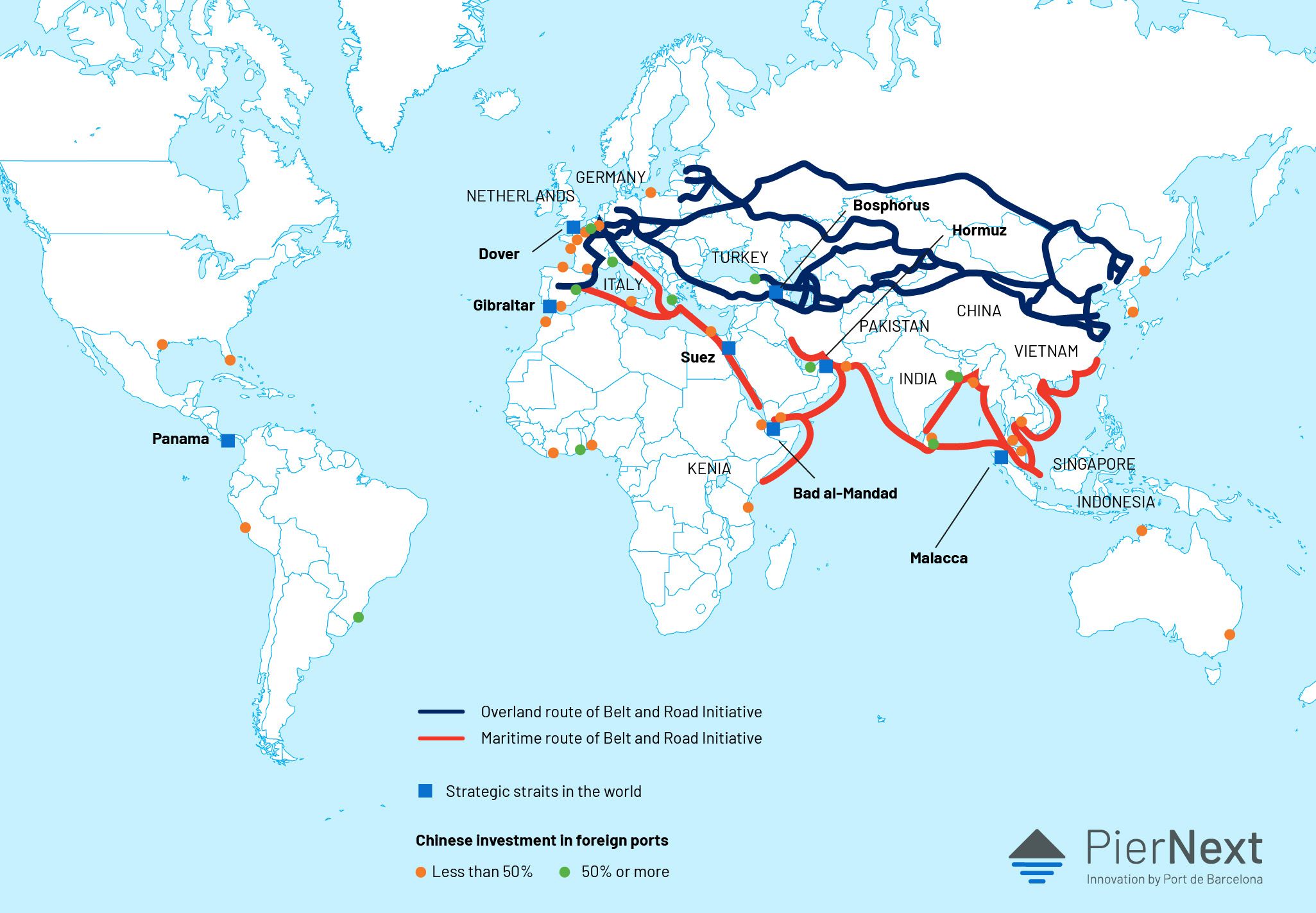

The BRI has two main focuses: the rail route between Europe and Asia and the sea route across the Indian Ocean and through the Suez Canal. (Gettyimages)

The BRI has two main focuses: the rail route between Europe and Asia and the sea route across the Indian Ocean and through the Suez Canal. (Gettyimages)

The New Silk Road: what next after COVID-19?

In 2013, Xi Jinping, President of the People’s Republic of China, announced the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a multi-billion euro project to create the Silk Road of the 21st century: a combination of overland and sea routes connecting Asia, Europe and Africa.

Jordi Torrent is the Strategy Manager at Port de Barcelona.

The BRI has two main focuses: the rail route between Europe and Asia and the sea route across the Indian Ocean and through the Suez Canal. (Gettyimages)

The BRI has two main focuses: the rail route between Europe and Asia and the sea route across the Indian Ocean and through the Suez Canal. (Gettyimages)

Some 25 million cargo containers moved between Europe and Asia in 2019. Approximately two thirds contained exports from Asia. This traffic is the world’s third largest trade route. It is a lot smaller than the first, the intra-Asia route, which sees the movement of more than 65 million containers a year. But it is comparable to the second biggest, the Pacific Ocean route, where about 26 million containers pass between Asia and America every year.

In 2018, more than 350,000 full containers were shipped between Asia and Europe by rail. Rail traffic between the two continents amounts to just 1-2% of maritime traffic. However, it is growing much faster than shipping. Whilst shipping has grown by less than 5% over recent years, rail freight has doubled its growth every year for the last 6 years. This is due in large measure to China’s support for the development of rail services between Europe and Asia as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launched in 2013 by Chinese President Xi Jinping.

The BRI is an idea promoted by the People’s Republic of China and its goals are to promote international trade and strengthen relationships between Europe and Asia. The initiative has steadily broadened its scope over recent years and now encompasses a wide range of projects on practically all five continents. From the outset, its aim has been to strengthen and develop logistics and transport infrastructure along Europe-Asia trade routes.

It has two main focuses: the rail route between Europe and Asia and the sea route across the Indian Ocean and through the Suez Canal.

Under the BRI, Chinese businesses, mostly state-owned, have built, acquired or been awarded maritime and rail infrastructure concessions in the main commercial transit points along both routes. For example, a number of companies — most notably COSCO and China Merchants Group — manage port terminals around the world’s five most important straits: Malacca, Hormuz, Gibraltar, Suez and Panama.

This is only the tip of the iceberg so far as the expansion of these businesses is concerned. Today, the Asian giant’s largest conglomerates control or hold stakes in about 20% of Europe’s port terminals. The figure is even higher around the Mediterranean. The prime example is the Port of Piraeus, which is managed by COSCO. In just five years, Piraeus has gone from being a small port to the main port in the region, handling in excess of five million containers.

The second principal element of the BRI is the promotion of rail connections between China and Europe. Before 2013, rail services between the two regions could be counted on the fingers of one hand. Seven years from BRI’s launch, they number in the hundreds and in the absence of official data it is reasonable to estimate that in 2019 they transported more than half a million containers.

Recipients of considerable government financial support, these services connect cities such as Wenzhou, Yiwu, and Xi’an with the principal European cities. The largest hubs are in Germany and Poland, from where the trains’ cargo is often distributed to the rest of the continent. Mention must be made of the longest route in the history of the world with more than 13,000 kilometres of track. It connects Yiwu (China), capital of consumer goods production, with Madrid in Spain. Similar services connect other Chinese cities with European cities including Paris, London, Hamburg, Antwerp, Lyon and Milan.

Rail vs sea

Rail vs sea

It is unlikely that rail could ever replace shipping for bulk cargo, given limitations that include lower capacity and operational constraints. As things stand, those limitations make the cost of transporting a container by train between China and Europe two or three times greater than using sea freight. Even with operational improvements and greater capacity, it will still be difficult for rail to compete on cost with sea transport.

Chinese rail operators run these services working with Russian, German and Kazakh operators. Chinese businesses have also built rail terminals and logistics areas along the route, especially at strategic points such as border crossings where containers are transhipped between trains. Noteworthy examples include the ports of Khorgos and Alashankou, where entire cities are being built to service Europe-Asia traffic.

Not to everyone’s taste

Over the last two years, the BRI has given rise to concern in some countries (India, Pakistan and some European nations) due to their loss of control to Chinese organisations and their strategic infrastructure. On the other hand, the United States has put pressure on some countries not to join the Asian giant’s initiative, either formally or informally. The outstanding example of that was the debate round whether Italy should join in early 2019, which the United States and even some European institutions openly opposed. Ignoring the criticisms, Italy eventually decided to join following the path taken by several Eastern European countries. Those countries are actively involved in the BRI, allowing Chinese businesses to set up and operate in their national port, logistics and rail infrastructure.

Consequences of the coronavirus

Consequences of the coronavirus

Lastly, we should ask ourselves: How might the COVID-19 crisis affect the BRI? Will China continue to drive the project forward or will it slowly walk away? It is hard to say. We should not forget that the People’s Republic of China has amended its constitution to include promotion of the BRI or that the project is one of the few expected to last until 2049, the constitution’s centenary year.

Most of the goals behind the BRI have already been achieved, thanks in part to the incalculable support of other global powers. China has become the main proponent of international free trade now that other global powers have become more protectionist or isolationist. The country’s businesses manage most of the main transit points for international trade. That means better connection for China’s inland regions to global trade along with greater access to and interchange with the central Asian republics with their natural resources.

Many countries around the world have been able in short order to complete infrastructure projects that had been languishing for years thanks to investment by the Asian giant. Others have managed to develop – at the price of significant debt.

The most likely scenario is that the BRI will continue but at a slower pace. China may re-focus the project on other regions such as Africa or other countries in south-east Asia. Time will tell whether the thousands of rail services now operating between China and Europe will be sustainable with lower state funding. However, it is hard to make predictions amidst the instability and uncertainty the world is currently experiencing.