In the last two years, projects and investments in wind propulsion systems have been multiplying. (bound4blue)

In the last two years, projects and investments in wind propulsion systems have been multiplying. (bound4blue)

Sustainable shipping invests in returning to sails

Wind as an ally for the sustainability of maritime navigation. It is not a vintage trend, as initiatives in the last two years prove. Strong investments in innovation and financing rounds in the most cutting-edge companies aim to transform the market share of wind propulsion from anecdotal to a reality. Can sustainable shipping do without fuels? We take a look at what's happening in the sector.

In the last two years, projects and investments in wind propulsion systems have been multiplying. (bound4blue)

In the last two years, projects and investments in wind propulsion systems have been multiplying. (bound4blue)

The growing role of wind propulsion systems in the decarbonisation of maritime transport is leading initiatives and investments by the European Union and other international institutions in 2023.

For example, Wind Energy Harvesting for Ship Propulsion Assistance and Power, WHISPER, an energy transition project aimed at retrofitting wind-assisted ships to achieve emission reductions, has received EUR 9.2 million.

Another EU-funded project is OPTIWISE, which investigates how to adjust the overall design of ships to optimise wind-assisted propulsion. The project, which will run until May 2025, will include 3 demonstration cases of wind propulsion concepts, as well as an overall design and architecture proposal and a novel energy management system linked to voyage optimisation for Wind S ships.

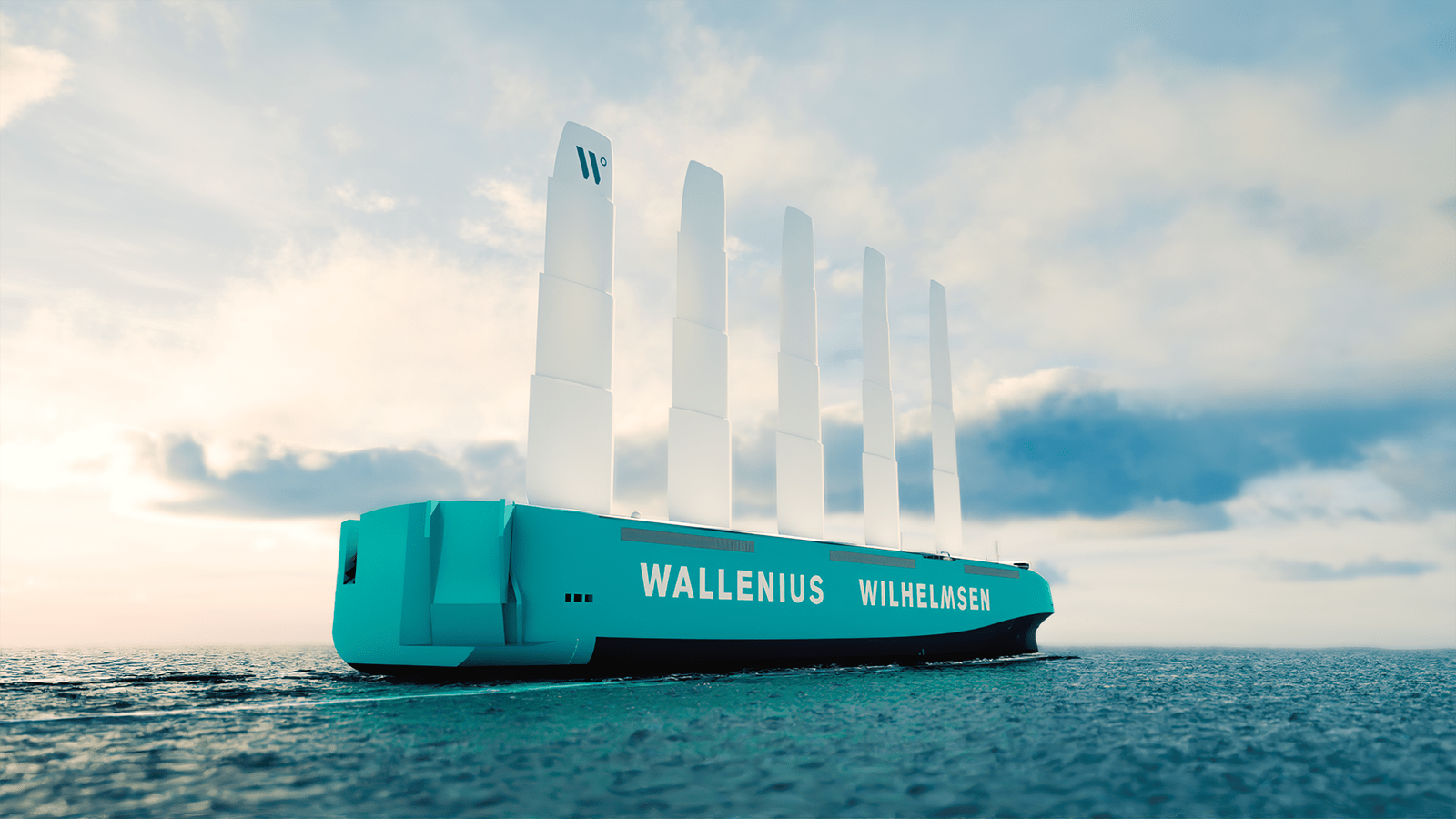

In terms of companies developing this technology, under the Horizon Europe project, the EU funded the construction of the Orcelle Wind, the first wind-powered Ro-Ro vessel, presented by Wallenius Wilhelmsen in 2021, with €9 million.

In 2022, Spain's bound4blue received a €4.1M grant from the Innovation Fund Programme, awarded by CINEA (European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency), in a €22.4M investment package that also includes corporate investors and venture capital funds. A year earlier, it received €2.4 million from the EIC Accelerator Program of the Horizon Europe programme. Other projects co-funded by the EU, and led by the Spanish company, are Greening the Blue and Aspiring Wingsails.

Cristina Aleixendri, co-founder and COO of bound4blue, explains to PierNext that they will invest these funds in increasing the commercial level of their eSAIL® suction sail system. "The objective of this round is, among other things, to keep improving the system. That means continuing to innovate and continue to make improvements to the technology."

Elsewhere, Winds of Change, a wind sail initiative by Smart Green Shipping, secured £60 million in funding under the UK Government's Zero Emissions Maritime Solutions programme. The funds will be used to design and build a 20-metre-high wing sail that will be the ultimate in wind sail technology called FastRig.

In Japan, several projects are underway:

Zephyrus Marine, Mirai Ships, Ad Hoc and SHIFT, signed a memorandum of understanding to build the Zephyrus Zero Carbon, an offshore wind service vessel (SOV).

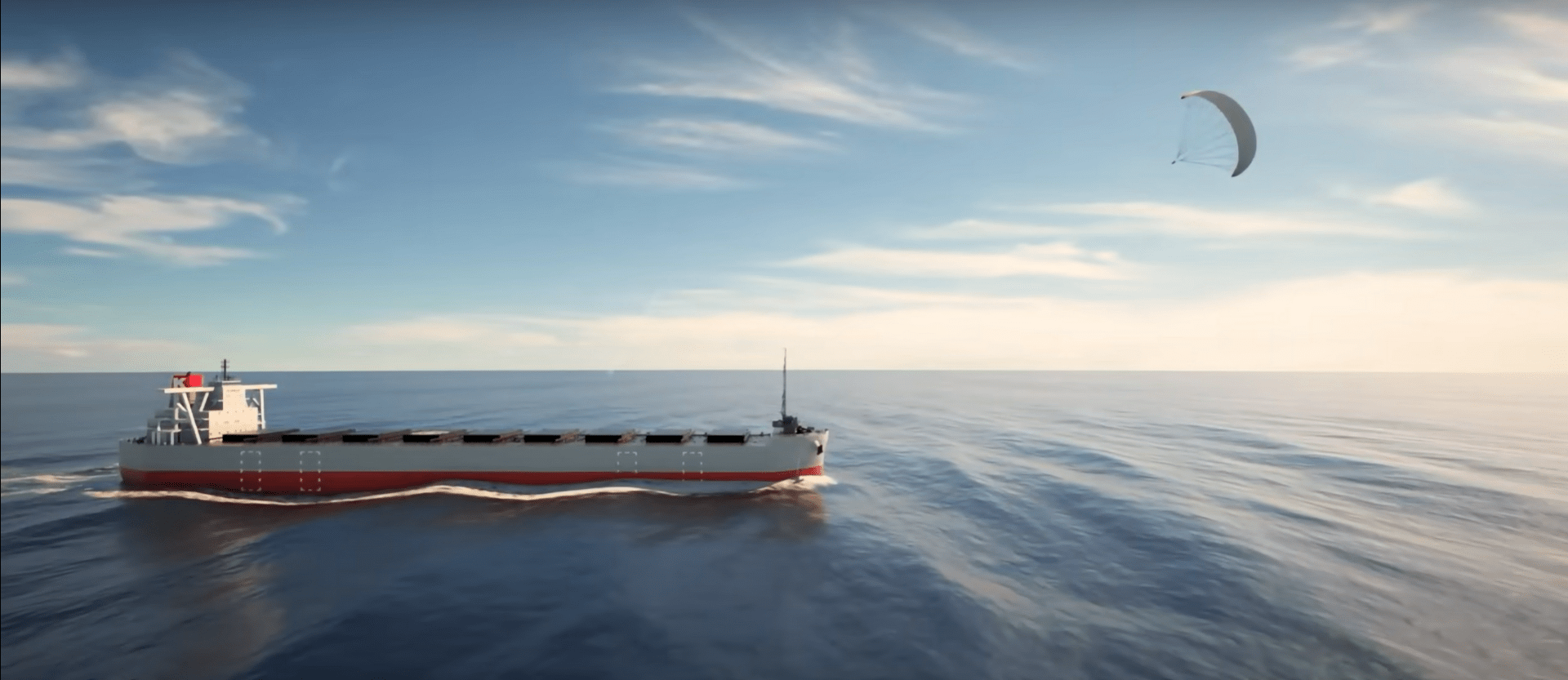

Last January, Japan's K Line and Electric Power Development Co (J-Power) unveiled plans to install Seawing, an automated wind-powered kite system, on the coal carrier Corona Citrus.

Finally, Japan's ONE recently revealed plans to install two wind-assist units on its 1036 TEU container ship "Kalamazoo" before the end of 2023.

The wind propulsion systems market

Currently, 24 ships are equipped with wind-assisted navigation systems (WASP). Although these figures will double by 2024, Aleixendri believes that it is too early to speak of technological maturity, as the implementation rate is very low considering that the world fleet of ships is around 120,000 units.

Currently, there are seven systems, of which the COO of bound4blue points to rotor and suction sails as the most mature. "For several years, there have been more rotor deployments, but it is expected that between the remainder of 2023 and next year, the number of suction sail installations will equal that of rotors," she shares. The technological top 3 is closed by rigid sails.

The seven systems are:

- Soft Sail – both traditional sail and new designs of dynarig etc.

- Hard Sail – wingsails, foils and JAMDA style rigs. Some rigs have solar panels for added ancillary power generation.

- Flettner Rotor or Rotor Sails – rotating cylinders operated by low power motors that use the Magnus effect (difference in air pressure on different sides of a spinning object) to generate thrust

- Suction Wings (Ventifoil, Turbosail) – non-rotating wing with vents and internal fan (or other device) that use boundary layer suction for maximum effect.

- Kites – the deployment of dynamic or passive kites off the bow of the vessel to assist propulsion or to generate a mixture of thrust and electrical energy.

- Turbines – using marine adapted wind turbines to either generate electrical energy or a combination of electrical energy and thrust.

- Hull Form – the redesign of ship’s hulls to capture the power of the wind to generate thrust.

There is the potential for 20-30% of the world's fleet energy requirements to be provided by wind propulsion systems as part of a hybrid approach

A tried and tested technology

In the case of bound4blue, in 2021 they installed a 12-metre suction sail on the fishing vessel Balueiro Segundo owned by shipowner Orpagu, becoming the first fishing vessel in the world to use it. Aleixendri details several changes that have taken place since then as a result of this first experience: from the aforementioned 12 metres, the company now offers three sizes; from 12 to 17 m, from 18 to 26 m and from 24 to 36 m.

This year, two 17-metre units have been installed on the Eems Traveller, a general cargo ship, using the third generation of the system, which includes aerodynamic improvements of 20%.

"In 2022, we carried out more tests in the wind tunnel, which together with the data obtained from the fishing boat and, to a lesser extent, from the Naumon, the travelling theatre ship of La Fura dels Baus, where we installed an 18-metre sail, have allowed us, for example, to improve the aerodynamic efficiency of the system," she explains.

Another innovation took place between the fishing boat and the Naumon; while in the former, the system was fixed, the latter incorporated the first folding system designed by the company that allows the sails to be folded. This was the second generation of the eSAIL®.

Other projects the company has underway include the installation of three 22-metre units on a Ro-Ro cargo ship in the fleet of Louis Dreyfus Armateurs, four sail units of the same height on a tanker owned by Odfjell and, lastly, a 26-metre-high system on a bulk carrier belonging to the Japanese shipowner Marubeni Corporation.

On the role played by shipowners willing to test wind propulsion technology, the aeronautical engineer explains that these are companies whose environmental efforts go beyond what is currently required by the various regulations and even seek to go further in reducing their environmental impact. "The growth has been quite organic," she says.

Their integration into ship design

Currently, given the current size of the world fleet, the majority of vessels incorporating this technology are existing. These are precisely the ones that need to make fuel and emissions savings to meet the decarbonisation targets set by the World Maritime Organisation and the European Union.

"In this case, a detailed engineering study is carried out with the shipowner to define where the system can be housed, which is defined according to many parameters. One, for example, would be at the operational level of the ship; if it has height limitations, sails of one size or another will be set, more or fewer units, which will be folding or not," she describes.

Wind-assisted propulsion regulation

Currently, wind propulsion is classified as a "fuel saving measure", a description that the International Windship Association is calling for to be changed to "propulsive power provider". The nuance that arises is: how is wind computed?

"Wind improves the ship's energy efficiency index at the Carbon Intensity Indicator level and at the EEXI or EEDI level, depending on whether it is a new or existing ship. It is good that the IMO incorporates wind in the improvement of these index, but they are not incorporated correctly as they consider them to be energy efficiency systems: adding a sail is like adding another engine to your ship, because in the end you use the wind, which is a fuel, which in this case is sustainable and free," she points out.

On the other hand, Aleixendri points out that European initiatives such as the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) or Fuel EU can give a big boost to clean technologies.

"Our clients with significant operations in European waters are seeing that the return on implementing our technology is the same, in terms of EU ETS and Fuel EU, as it is in terms of fuel savings," she says.

Although wind propulsion technology still has a low share of deployment, members of the International Windship Association say in a joint statement that there is the potential for 20-30% of the world fleet's energy requirements to be provided by wind propulsion systems as part of a hybrid approach to propulsion.

A study commissioned by the UK government forecasts up to 45% penetration of wind technologies in the global fleet by 2050, the brief notes. A key report on wind systems commissioned by the EU estimates the possibility of up to 10,700 installations by 2030, including approximately 50% of bulk carriers and 67% of tankers.