As of December 2019, a total of 136 countries and 30 international organizations have signed cooperation documents with the Chinese project. (Belt and Road Initiative)

As of December 2019, a total of 136 countries and 30 international organizations have signed cooperation documents with the Chinese project. (Belt and Road Initiative)

Ports on the new digital silk road

The endeavour for geo-commercial control has already begun. The China-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is described as a ‘globalization 2.0’ by its supporters and as ‘Marshall Plan’ or ‘neocolonialism’ by its critics. Technology and infrastructure aim to unite the five continents in an unprecedented project.

As of December 2019, a total of 136 countries and 30 international organizations have signed cooperation documents with the Chinese project. (Belt and Road Initiative)

As of December 2019, a total of 136 countries and 30 international organizations have signed cooperation documents with the Chinese project. (Belt and Road Initiative)

“It is the project of the century.” This is how Chinese President Xi Jingping introduced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, an ambitious plan that aims to logistically connect Asia, Europe, Africa and Oceania by land and sea routes, emulating the historic Silk Road that commercially united the Far East with the West.

As of December 2019, a total of 136 countries and 30 international organizations have signed cooperation documents. Agreements have been sealed for the construction of infrastructure worth 400,000 million dollars and Chinese investments total 90,000 million dollars. Currently, more than 100 projects are underway in sectors such as transportation, energy, mining, telecommunications, industrial parks, Special Economic Zones, tourism and urban development, as well as the creation of six economic corridors. The project is expected to generate 55% of the world's Gross Domestic Product.

The digital silk road

In 2015, Xi Jingping added the D for digital to highlight the importance of global connectivity and boost the internationalization of local tech companies. In 2016, the digital economy accounted for 31% of the Asian giant's Gross Domestic Product. Furthermore, Chinese e-commerce accounted for 42% of the global market in 2017.

According to the Digital Belt & Road Research Center of Fudan University, 201 Chinese companies working on digital transformation have implemented 1,334 foreign investments in eight sectors since 2018: ecommerce, communication infrastructure and 5G, fintech, smart cities, industrial internet of things, smart terminals, information technology, media and entertainment. 37% of these projects are located in Asia, 12% in Central and Eastern Europe and Russia and 8% in Africa. 57% of these investments are associated with the BRI.

Some examples of these digital investments are the following:

Huawei is testing its technology for smart cities in more than 160 cities from 40 countries after a trial in Shenzhen, where waiting times at the airport (with volume of 50 million passengers per year) have been reduced by 15% thanks to facial recognition technology and data analytics, which have decreased the need for manual passport controls.

In terms of telecommunications infrastructure, China Telecom, China Unicom and China Mobile are developing terrestrial cable links between Europe and Asia. Huawei has a leading role in African infrastructures and ZTE is building fiber optics in Afghanistan. These investments aim to integrate these countries, traditionally more disconnected, into this digital ecosystem.

The four basic digital axes of the BRI

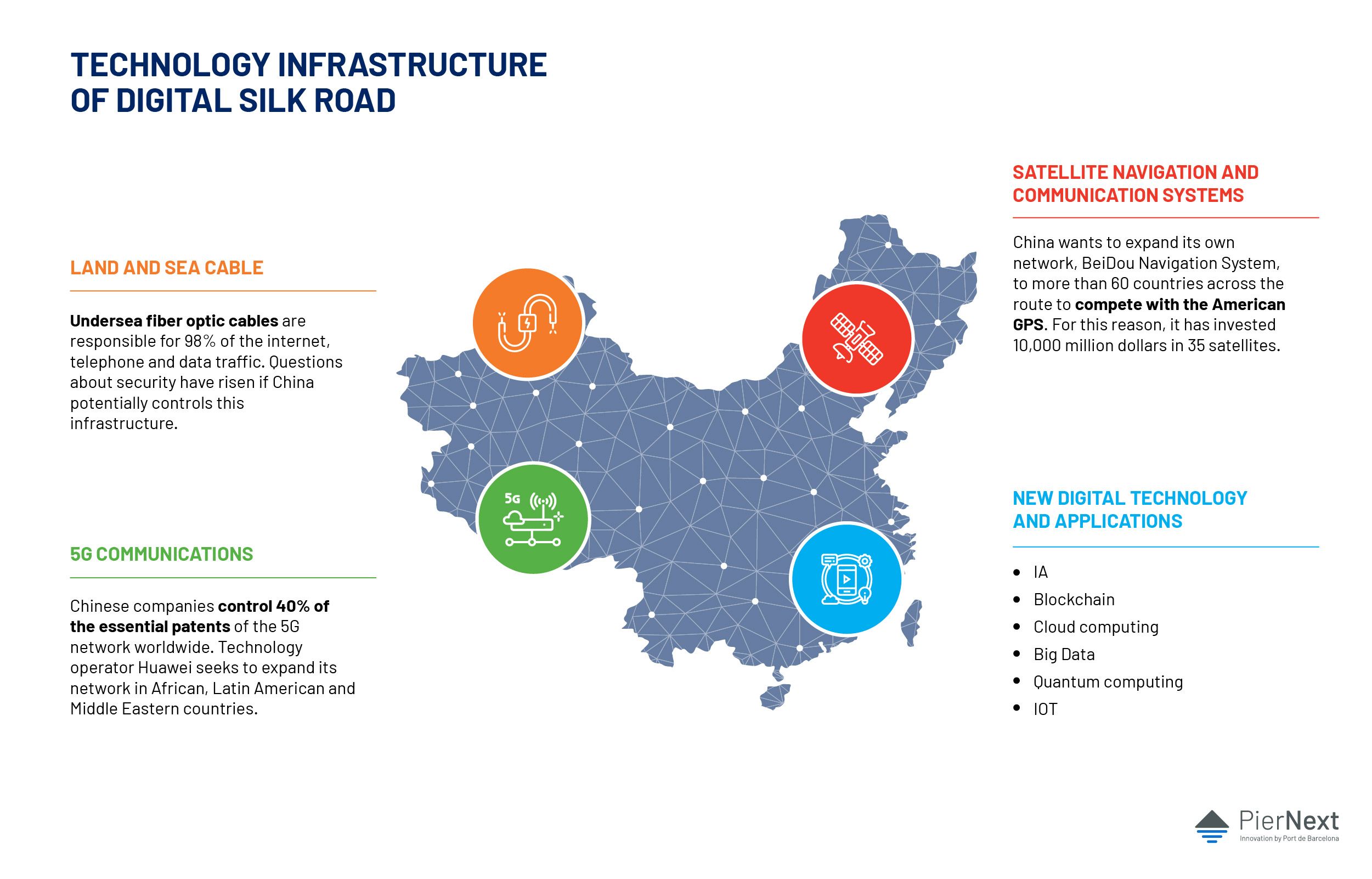

The Chinese digital strategy is divided into four points:

- Undersea fiber optic cable links are responsible for 98% of internet, data and telephone traffic. Mostly controlled by the United States, this imbalance worries China because it poses a security issue. It seeks to level the balance and thus, Huawei Marine Networks and Co. has worked on more than 90 projects to build and improve undersea fiber optic networks, among which there’s the 6,000 km connection between Brazil and Cameroon, built at the end of 2018. Works have also started in 2019 for the more than 12,000 kilometers that will connect Europe, Asia and Africa.

- Another key point, and also a source of friction with the US, are 5G communications on which capabilities like Artificial Intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), robotics and cloud computing will be deployed to generate new business models. According to the Eurasia consultancy, Chinese companies own 40% of essential patents for 5G networks. China has moved quickly into African, Latin American and Middle Eastern countries. Egypt and Tunisian operator Ooredoo Tunisie have held meetings with Huawei to discuss the possibility of launching a 5G network in their respective countries. On the other hand, the United States, Canada, Japan and the United Kingdom have closed their doors to the company alleging risk of espionage.

- Precisely, the third axis is based on all these technological applications with which China wants to become a cyberpower. According to the Digital Economy Report 2019, the US and the Asian country generate 75% of blockchain patents, invest 50% in IoT development and represent 75% of the cloud computing market. China has already overtaken the United States as the largest hub of unicorns (start-ups valued at more than 1 billion dollars), a sign of its determination to master new technologies.

- Satellite communication and navigation systems are the last axis. The Asian country wants to extend its own network, BeiDou Navigation System (BDS), to more than 60 countries along the route to reduce its dependence on the American GPS, as Europe does with the Galileo system developed by the EU and the European Space Agency. Thus, China will increase its diplomatic influence in regional and international forums on issues related to position, navigation and time (PNT). China has invested 10 billion dollars in 35 satellites and ensures that BDS promises better and more accurate global navigation coverage, as well as being the first system in the world that combines communication and navigation with a margin of error of 10 centimeters against GPS’ 30 centimeters. Its higher bandwidth enables the transmission of video and large volumes of documents. BDS technology is already exported to more than 100 countries. Currently, with 30 satellites in orbit, it can already cover the whole planet.

A total of 136 countries and 30 international organizations have agreed the construction of infrastructures worth 400,000 million dollars

The fitting of ports

Digitally speaking, China is committed to unifying ports and their logistic operations under the same electronic communication platform, which would also include rail transport to create a single multimodal system. The difficulty lies in the ability to digitally integrate all the ports that form the route.

The BRI maritime route seeks to link Chinese and European ports through the South China Sea, the southern Pacific and the Indian Ocean. In this ecosystem, ports become hubs. In this sense, the Chinese vision consists of connecting ports to a global supply chain to turn them into intelligent infrastructures, to ensure supply lines for energy resources and raw materials.

To fulfil this, the initial focus was to build physical infrastructure, but it soon shifted towards a more digital vision through a common platform that facilitates transport planning and a multimodal logistics system, as the global supply chain is being redrawn by cross-border data flows enabled by digital platforms.

The main challenge lies in the development of a standard electronic data interchange (EDI) and application programming interface to allow the different operational data systems communicate with each other, leaving aside security and sovereignty issues.

In terms of physical infrastructures, the most advanced BRI port projects have been based on existing routes: Piraeus (Greece) and Djibouti (Africa). Little progress has been made in projects related to alternative routes, such as the construction of a new canal in Nicaragua.

Question marks and business impact

The Asian Initiative doesn’t lack controversy over freedom, security and trade. Technologically speaking, two models confront: an open and transparent network that facilitates global free market trade encouraged by the US, and the Chinese model, based on a closed information technology network using its own systems, something that defies European Union regulations.

With regards to logistics and infrastructures, this macro enterprise is encountering several stones along the way. Doubts have been raised about the viability of some projects due to the debts they generate in recipient countries. The operations of the port of Djibouti, in East Africa, for example, were handed over to China due to non-payments. Almost 10% of the world’s oil exports, and 20% percent of commercial products, navigate through the Suez Canal, travelling close to the African country.

On the other side of the coin, some governments see in China an example of a successful economic alternative to the prescriptions of the International Monetary Fund and the Western model, and see in the BRI a way to emulate this growth.