Donald Trump and the (relative) logistical relief of the Panama canal

A consortium led by the American BlackRock will buy from China's CK Hutchinson its ports in the Panama Canal. The agreement, made public only one day after Trump once again claimed control of the canal during the union speech, may lower the geopolitical tensions that he himself has created since the beginning of his second term. All in all, the debate over the future of this infrastructure is still open and projects for new alternative crossings continue to emerge.

The year 2025 began with logistical tension at one of the main sea crossings.

- Donald Trump opened his term in office by all but threatening to invade Panama to regain control of the canal. In fact, he went so far as to accuse China of operating “lovingly, but illegally, the Panama Canal”.

- He then added that “China is administering the Panama Canal even though it was not given to China, it was given to Panama foolishly, but they violated the agreement, and we are going to get it back or something very powerful is going to happen”.

- Finally, in the union speech last March 4, he insisted that the U.S. was going to recover the Panama Canal: “The Panama Canal was built by Americans for Americans, not for others, but others could use it,” Trump said.

- A day later, CK Hutchison Holdings Group announced the decision to sell its 90% stake in Hutchison Ports PPC (Panama Ports Company) to the consortium formed by the US investment company BlackRock and the investment fund Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP), together with Terminal Investment Limited (TiL), the terminal operator of the shipping group Mediterranean Shipping Company, for 22.8 billion dollars. The consortium also takes stakes in other ports around the world and although the firms assure that the deal has nothing to do with Trump's pressure, it certainly contributes to easing geopolitical tensions.

In addition, pressure from the new Trump Administration seems to have paid off and the Panamanian government of President José Raúl Mulino announced that his country would abandon the Belt and Road initiative - driven by China and also known as the “New Silk Road” - in 2026, when it was due to be renewed for a new three-year period.

Beyond satisfying White House ambitions, Panama's resignation is loaded with a certain symbolism, as it was the first Latin American country to join the Belt and Road initiative in 2017, followed by Venezuela, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Argentina, Bolivia, Uruguay, Costa Rica, El Salvador and Cuba.

Alexander Eslava, port consultant and international logistics expert, in conversation with PierNext, considers anyway that “without the Silk Road, China has been a leading player in Latin American investments for more than a decade, where its development banks have lent more than US$150 billion in the last 15 years”.

Still, Trump seems to have gotten away with it.

But that has not prevented the reopening of the debate on new sea passages that could serve as an alternative to this connection between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Because the Panama Canal has not only attracted attention recently because of the ambitions of the U.S. president:

- Climatic issues and the difficulties in handling a greater volume of maritime traffic on this route have also raised doubts about its future viability. Because of this combination of factors, there has been talk of other alternative passages to facilitate navigation between the two shores of the American continent.

The limitations of the Panama Canal

The Nicaragua Canal, the Northwest Passage through Canada, the Tehuantepec corridor or Colombia's dry canal are some of the alternatives to the Panamanian route that are being considered. These are not magic solutions. All of them have their pros and cons to consolidate themselves as authentic and reliable alternatives, but they can have a lot to say in the international maritime scenario of the coming decades.

Beyond President Trump's ways of exercising diplomacy, the truth is that the Panama Canal has been a key infrastructure for the U.S. since its commissioning in 1914.

- According to data from the Panama Canal Authority (ACP), 52% of maritime transits through the infrastructure had origin or destination in a U.S. port.

- Similarly, and according to the same source, the percentage rises to 76% when looking at the volume of cargo transiting the Central American route to or from a U.S. port.

But the Panama Canal has long cast doubt on its future beyond a geopolitical tug-of-war between Washington and Beijing over its control. The infrastructure has shown itself to be particularly vulnerable to the effects of extreme weather. The effects of El Niño during 2023-2024 (decrease in rainfall) lowered the water level in the Gatun reservoir and Lake Alajuela, which are essential for the normal operation of the infrastructure.

Going into detail, and according to ACP data, maritime traffic was reduced to a minimum of 18 daily transits in February 2024. Pre-El Niño normality was not recovered until September of that same year, when it was possible to return to 36 transits every 24 hours.

The phenomenon affected a large part of the Latin American Pacific basin. In addition to Panama, countries such as El Salvador, Nicaragua, Peru and Ecuador suffered a reduction in port traffic of between 10% and 25% as a result of the effects of El Niño.

In addition to the consequences of weather effects, the Panama Canal has other weaknesses, such as the capacity for larger displacement merchant ships to operate. The infrastructure can accommodate vessels of up to 17,000 TEU - a record set by the container ship MSC Marie in the summer of 2024.

Despite this milestone, we must not lose sight of the fact that the Panama Canal does not have the capacity to accommodate the passage of the large merchant ships that ply the seas and oceans, with capacities of more than 24,000 TEU. Currently, these vessels have to transit the Cape of Good Hope on routes between the Pacific and the Atlantic.

Nicaragua's canal, a reliable alternative?

In view of the geopolitical, climatic and technical doubts that loom over Panama, other maritime crossing projects have begun to be discussed. One of the most outstanding because of the interest it has aroused is the Nicaragua Canal. For the moment, it is a project on the table, but, if it comes to fruition, it would be a serious competitor to the traditional Central American route.

Actually, it is not a new idea. Since the years of Spanish colonization, projects have been proposed to join the two oceans through Nicaragua, and even the United States considered it as a possibility in the 19th century, although it finally opted for the Panamanian route. Other powers such as France also analyzed projects in the area.

But if we look at more recent times, the current project dates back to 2013, when the National Assembly of Nicaragua approved the concession to build a canal to the Chinese company HK Nicaragua Canal Development Investment. Four years later, with the good relations between Beijing and Panama, it seemed that the project promoted from Managua would not prosper.

The Nicaragua Canal seemed to be forgotten until the end of 2024, with the logistical aggressiveness of Donald Trump. President Daniel Ortega presented a new project at the XVII China-Latin America and the Caribbean Business Summit, held in Managua.

With a budget of US$50 billion, the proposal sought to attract Chinese companies once again, and included a route of 278 kilometers and a width of between 230 and 520 meters. As Eslava explains to Piernext, “the project this time presented a new route in which, instead of crossing Lake Cocibolca, it would pass through Lake Xolotlán, given the drought in Lake Gatún, the main supplier of fresh water to the Panama Canal”.

Continuing with the details of the proposed route, it would start from a port that would be built in Bluefields, capital of the Autonomous Region of the South Caribbean Coast, pass through the central part of Nicaragua, through Lake Xolotlán and exit at the port of Corinto, on the Pacific coast of Nicaragua.

- The advantages of this theoretical infrastructure with respect to the Panama Canal would be that, with a depth of between 26 and 29 meters, it would allow the traffic of ships of greater draft. In addition, the navigation distance between the U.S. Pacific and Atlantic coasts would be reduced by 900 kilometers.

According to sources, daily transit estimates suggest that between 13 and 16 ships could sail through this infrastructure daily. Less than half the capacity of the Panama Canal at full capacity, but this difference would be compensated because the Nicaraguan route would transit ships of a much larger displacement.

Beyond the financial and technical feasibility of the project, the Nicaragua Canal has other challenges. As we have seen, like the Panamanian route, the area is sensitive to climatic phenomena such as El Niño. In addition, the development of its works may have a very strong environmental impact in areas such as Lake Cocibolca, with an extension of 8,264 square kilometers.

Interoceanic corridor of Tehuantepec, Mexico

Alternatives to the Panama Canal do not always involve major sea lanes. There are mixed projects that combine land transport -either road or rail- and link two port points on each of the oceans. Known as land bridges, they also have strengths and weaknesses.

One of the reference projects in this field is the Tehuantepec interoceanic corridor in Mexico, which would connect the port of Coatzacoalcos with Salina Cruz on the Pacific along some 303 kilometers. Again, this is an idea with a long history, since it all began in 1907 when the first rail connections were created to link the states of Oaxaca and Veracruz.

Today, there is a desire to expand not only the railway lines but also all the facilities required for this Tehuantepec corridor to be an alternative to the Panama Canal (such as airports, industrial parks, maritime and river infrastructures or airports, among others). To develop it, “there is an estimated investment of 4,343 million dollars”, according to Eslava.

With the Panama Canal crisis caused by El Niño, the government of the former Mexican president, Manuel López Obrador, rescued it from oblivion. Although there is a certain consensus that, due to the volume of goods expected to be moved - 1.4 million containers per year, according to Mexican government data - it is more likely to be a complement than a competitor to the Central American waterway.

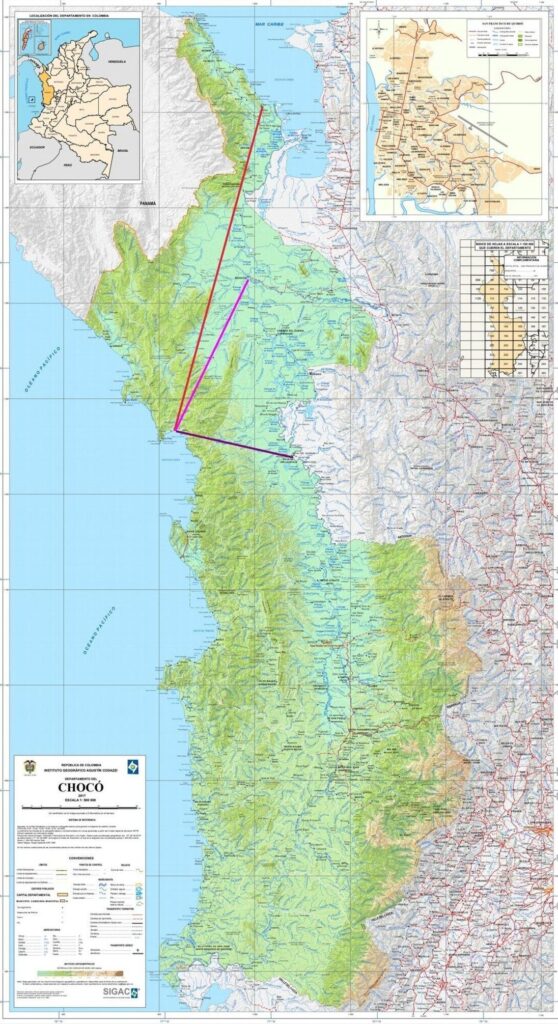

Canal Seco, Colombia

Another major emerging economy in the region, Colombia, is also betting on its own corridor, known as the Canal Seco, which would link the port center of Buenaventura, on the Pacific, with Cartagena de Indias, on the Atlantic.

As strengths of this route, Eslava highlights that the Buenaventura complex “has three terminals for container ships managed by three port operators and between them they have 10 docks equipped with 21 gantry cranes, which gives them a good capacity to move transshipment containers”.

Canada and the U.S. also have land bridge routes to promote various rail corridors through these two extensive countries with hundreds of kilometers of coastline on both oceans. However, the saturation of some sections and the high labor costs mean that for the time being they are not an alternative to Panama.

Given all these land route projects throughout most of the American continent, Alexander considers that they are not a great competition for maritime routes: “maritime and river/lakeway transport are the ones that generate lower logistics costs in the transport of goods, and much more (economy of scale) if the goods are moved in ISO intermodal sea containers”.

Northwest Passage

Another maritime alternative to connect the Atlantic and the Pacific is the Northwest Passage. An old dream in navigation that dates back to the 16th century when England wanted to avoid the control of the Portuguese and Spanish over the trade routes to the rich markets of Asia.

This route was discarded for a long time because it was blocked by ice, but since 2001, global warming has increased the periods of time in which it is possible to navigate these waters. A trend that will increase according to several scientific reports.

This is one more navigation route through the Arctic that has aroused so much geopolitical interest in recent years due to the convergence of interests of powers such as China, the U.S. and Russia, in addition to the defense of their sovereignty by local actors such as Canada and Denmark.

In the case of the Northwest Passage, it runs through US and Canadian territorial waters. Trump has also set his sights on this route to ensure US economic and political hegemony, although Alexander Eslava considers that “the main challenge [of this route] is to see how the thaw ends up shaping navigation through these waters in the coming decades.”

For the time being, what Trump has achieved is a thaw in the Panama Canal. We will have to see how the new management of the Canal ports evolves and what happens with the alternatives for passage. What no one can deny is that logistics has been in the news as rarely in recent times.