This trend began to spread in mid-2021, especially on the trans-Pacific stretch between Asia and the West Coast of the United States. (GettyImages)

This trend began to spread in mid-2021, especially on the trans-Pacific stretch between Asia and the West Coast of the United States. (GettyImages)

From Just in time to Just in Case: why large retailers are setting up their own logistics network

Maritime services have lost reliability, and this is causing the shortage of products on shelves and in warehouses, affecting the reputation of retailers and marketplaces. These have responded by taking control chartering ships and containers. Will this business model, unthinkable just a couple of years ago, remain?

Olga Salvador is the BCO’s & Reefer Manager at the Port of Barcelona.

Carles Mayol is the Head of Container Division at the Port de Barcelona.

This trend began to spread in mid-2021, especially on the trans-Pacific stretch between Asia and the West Coast of the United States. (GettyImages)

This trend began to spread in mid-2021, especially on the trans-Pacific stretch between Asia and the West Coast of the United States. (GettyImages)

Retailers take control by leasing their own ships and containers

Covid-19 has brought a paradigm shift in a wide range of areas. The chain of disruptions unleashed in the transport and logistics sectors has generated a context of unreliability and lack of services that has, among its many consequences, created a new business model: part of the large-scale distribution has decided to take the reins by acquiring and renting vessels and containers to manage its own logistics.

Due to the initial uncertainty caused by the expansion of Covid 19, shipowners opted to reduce space supply with a strategy of blank sailings. The unexpected growth in demand for consumer goods in the following months led to a situation of mismatch between supply and demand which acted as a trigger for the context in which we find ourselves today.

Although ships resumed their services fairly quickly, the consequences of this initial disruption still linger to this day: congestion in ports, increased transit times for ships, and a huge drop of maritime services' reliability. This last point is critical, as product shortages directly affect the reputation of retailers and marketplaces.

Only 1 in 3 ships are on schedule

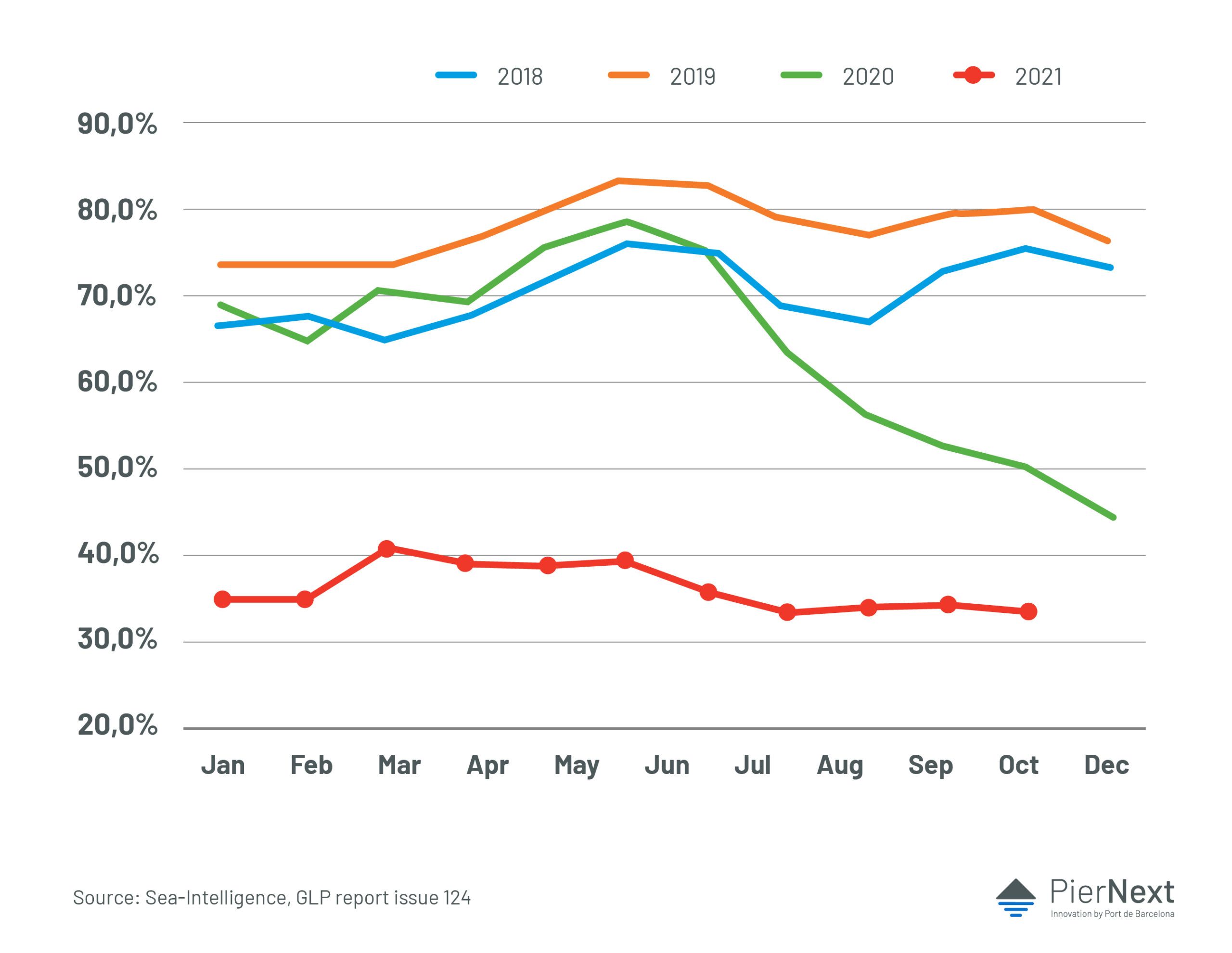

Reliability, or Just in Time, which was 90% a decade ago and 80% before the Covid-19 pandemic, has plummeted to 33%. This means that only one in three ships is on schedule. Unreliability and rising service costs have led the Beneficial Cargo Owners (BCO's), i.e. the large distributors, to become directly involved in the management of their transport in order to deal with this situation.

If we look at transpacific traffic (which has traditionally belonged to the three maritime alliances that serve the East-West routes: Asia-Europe, Europe-US and US-Asia) we observe how the alliances' share on this route has dropped from 82% to 67.7% due to the emergence of new players.

This is mainly due to two realities. On the one hand, the increase in the percentage of shipowners' services operating outside these alliances. On the other hand, it reflects the increase in the volume of traffic handled directly by independent operators, which are the BCO’s.

Retailers have decided to take control and manage the transport of their goods, as the reputational risk and the cost of not having products on their shelves is higher than the price of these freights

From a 'port-to-port' to a 'door-to-door' service

After years of oversupply and extremely low reight rates, this shift has led to a sudden and sustained increase in freight rates, reaching levels we've never seen before.

Thus, after years of economic losses that led, for example, to the bankruptcy of the Hanjin shipping line in August 2016, shipowners find themselves in a new context of positive economic results that have accelerated the processes of vertical integration already predicted before the pandemic.

With their pockets full, shipowners have started to acquire logistics, freight forwarding, technological development companies linked to shipping, ecommerce or last mile with the intention of integrating them into their business vertical and moving on from offering a 'port-to-port' service to a 'door-to-door' one.

This situation generates an action-reaction effect. Freight forwarders and logistics operators, customers of shipowners and responsible for 70% of their cargo, are in turn developing strategies to avoid being left out of this new paradigm, opting for horizontal integrations with other forwarders and operators but also embracing other areas such as the purchase of container terminals, as seen with some Chinese logistics operators.

Against this backdrop, there is another trend that has been accentuated in the last year and a half as a result of the loss of reliability and high freight rates. Big retailers with large logistics departments have decided to take the reins and manage the transport of their goods buying or renting containers and chartering ships, as the reputational risk of not having products on their shelves is higher than the cost of these freights.

This trend started to spread in mid-2021, especially on the transpacific leg between Asia and the West Coast of the US.

The rules of the game have changed

The predictability and controlled scenarios of the Just in Time have been left behind, changing the rules of the game. Now, the actors who were previously clients of the shipping companies have reversed their roles: Just in Time has been replaced, in many cases, by Just in Case.

These types of solutions are not added from one day to the next, but rather there is prior work in the purchase or leasing of containers and ships, definition and optimisation of routes, management with maritime terminals, search for spaces for depositing and handling the containers, etc.

It is a path that is not without its problems either, since, as has happened with freight rates, the price of containers and ship charters has multiplied in recent times. Before Covid-19, a dry cargo container cost around $1,500-2,000. Today, the cost is between $7,000-7,500.

It all started with Amazon

Amazon started this path in 2016, when it received a licence from the Federal Maritime Commission to operate as a Non Vessel Owning Common Carrier from China to the United States.

However, this new operation and role does not apply to all of its products, only to those considered key to cover its basic products or those destined for specific commercial campaigns. For the rest, they continue to use traditional transport channels.

Examples of large retailers becoming maritime operators

- Ikea

Ikea confirmed in September 2021 that it had begun chartering ships and purchasing containers to ensure the availability of goods in its shops.

Incidents such as the Ever Given caused months of delays in completing shipments and shortages of raw materials, coupled with disruptions in the global supply chain, were causing shortages and stock-outs in its shops.

- Lidl

In Europe, the supermarket chain Lidl (Schwarz Group), under the name of Tailwind Shipping Lines, has launched its own shipping operator in order to cope with continuing supply chain problems. This shipping line will allow the growing production volume of all its facilities to be managed in a more flexible way in the long term. Although it initially considered investing in an existing shipping company, it has finally decided to set up its own.

- Coca-Cola

On October 1, the corporation announced the chartering of three bulk carriers to transport more than 60,000 tonnes of raw materials to its global chain of production units. The contracted vessels are the 35,009 dwt WECO LUCILIA C, owned by AM Nomikos, the 34,399 dwt APHRODITE M, provided by Empire Bulkers, and the 35,130 dwt ZHE HAI 505, owned by Zhejiang Shipping.

These are just a few of the many examples we can find, such as Alibaba, Walmart, Target or COSTCO.

Although no figures published on the reliability improvement that these large distributors may have experienced, there are imponderables from which they are not exempt from (such as port congestion, especially in the USA and China due to blockades and closures, or the war in Ukraine). However, managing and controlling all the information is key in a logistics context such as the current one.

Future prospects. The implications of this movement

It is not easy to anticipate whether or not this model will be consolidated over time. As long as the service has fulfilled its function, no major interventions have been necessary. However, the pandemic has revealed that the correct performance of transport and logistics is also a crucial element of their business.

While it is true that we are referring to a very specific market sector, not all large companies can manage this type of operation. It is unlikely that this trend will put logistics operators or shipping companies in check but we must be vigilant about any trends changes within the sector and adapt quickly to serve the unmet needs of these new players.

For the time being, this trend will continue during the contractual period stipulated in the chartering of ships and containers by these companies (between two and three years) or as long as the situation of unreliability and low service standards persists.

A recent survey in the first quarter of 2022 indicates that reliability has increased slightly, from 33% to 35%. Several models predict that it will gradually recover until it reaches a substantial improvement by early 2024.

Still, it should come as no surprise if in the future large BCO's continue this strategy for at least those product lines where availability and Just-in-Time delivery is critical.

If a few years ago we were dealing with a context of concentration and alliances between shipping companies, it would not be unreasonable to think that the large BCO's could also begin to weave synergies and collaboration channels to continue to enter this part of the business.