Major waterworks throughout history

From the Pharaohs' Canal to Suez and Panama, great waterworks have shaped global trade and geopolitics throughout history. All great civilizations have aspired to dominate the seas. Sometimes geography presented difficulties in gaining control of shipping routes, and there were always interests that marked their birth and development. The same as we are seeing now, old problems, challenges and tensions... in the age of AI.

The Suez Canal, a project of Caesars and Pharaohs

The great civilizations at the origins of human history - Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, China, etc. - showed an early interest in hydraulic works. At first, they developed these infrastructures to control the fluvial environment, whether it was the Nile, the Euphrates or the Yellow River.

The next step was to seek to improve their ability to navigate in areas where the geography presented some difficulty. An old aspiration, but one that is also on the agenda of the great powers of the 21st century, as can be seen by the interest of the major international players in seeking new routes through the Arctic or defending key points for navigation such as the Red Sea.

For example, today's Suez Canal is an ancient dream that began in the 12th Dynasty of the kings of Ancient Egypt. Pharaoh Sesostris III ruled between 1878 and 1839 B.C. He was the first to link the Nile Delta with the Red Sea. His aim was to trade with places in the horn of Africa, such as the country of Punt.

The problem for Sesostris III, as Aristotle notes in his work Meteorology, was that “the sea was higher than the land”. The pharaoh had to stop the works to prevent the sea water from invading the Nile delta. Several successors of this Egyptian monarch tried to complete the project but with the same result.

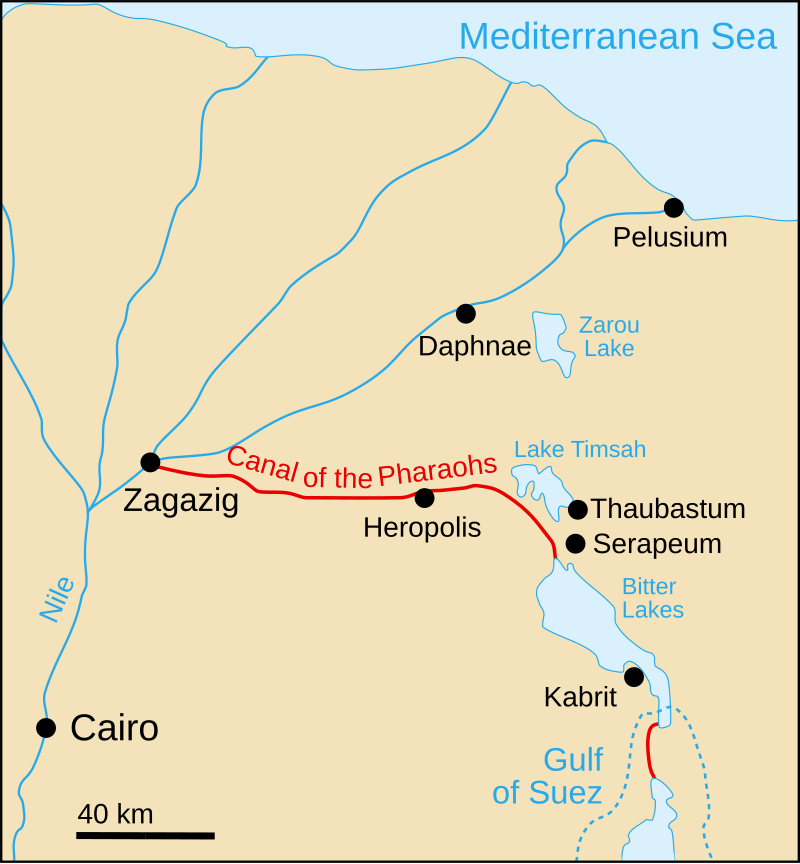

Canal of the Pharaohs

Everything would change in 273 BC. Pharaoh Ptolemy II's engineers created a system of locks. This prevented the waters from mixing and, thus, the Canal of the Pharaohs became a reality. It linked a point near Cairo with the port of Arsinoe in the Heroopolitan Gulf (as the Suez Canal was then known).

The Romans followed this commercial policy when they took control of Egypt in 30 B.C. They even improved the Canal of the Pharaohs. This infrastructure would be in use until 767, when revolts by the local population against the Abbasid Caliphate destroyed the infrastructure.

The Grand Canal of China

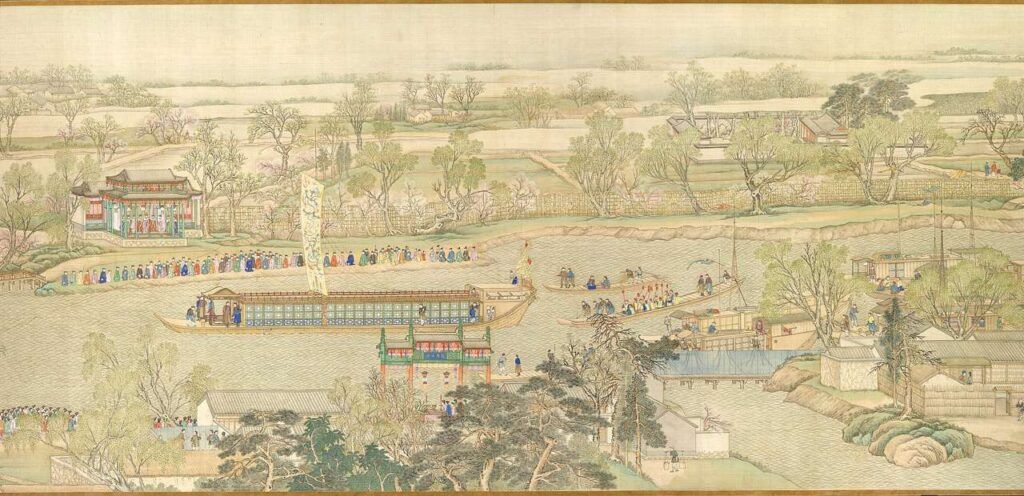

China can boast of having the oldest hydraulic work still in operation. We are referring to the Grand Canal, declared a World Heritage Site in 2014 by UNESCO. Its nearly 1,800 kilometers in length began to be built in the 5th century A.D. and the main sections were completed around 609 A.D. in the time of the Sui dynasty, combining artificial canalizations with natural river courses.

The Grand Canal would be an important tool for the structuring of the Chinese territory, which has not always been unified in its millenary history. One of the first advantages it brought was lowering the cost of transporting grain from the Yangtze Delta and the north of the country.

In terms of maritime transport, the Grand Canal was a great auxiliary tool. The Tang (618 - 907 AD) and Song (960 - 1279 AD) dynasties opened up to trade with other parts of the world.

Pirates and decadence of imperial China

At different times in history, Chinese dynasties faced challenges similar to those posed today by Houthi attacks. Piracy was a frequent problem in the seas of Asia and the Grand Canal became an alternative transport route to avoid raids in areas such as the South China Sea or the Taiwan Strait.

The decline of the Grand Canal paralleled that of imperial China during the 19th and 20th centuries. The lack of maintenance and the development of new transportation routes, such as the railroad, marked a slow decline.

Today, the Grand Canal runs between Beijing and Hangzhou, although only a small final stretch is navigable. Ports such as Huanghua, one of the most booming in China, benefit from this infrastructure to boost the transport of resources as vital to the country as coal.

The Corinth Canal

If we look at Europe, in Ancient Greece the construction of a canal across the isthmus of Corinth was considered to avoid circumnavigating the Peloponnese peninsula, i.e. to shorten 700 kilometers. The first to do so was Periander, tyrant of Corinth in the 7th century BC, but he saw that it was unfeasible and opted for a system of ramps that would allow ships to be dragged across the mainland.

Emperor Nero in the 1st century A.D. and the Venetians in the 17th century A.D. tried to revive the project without success. It was not until 1870 that the Greek government - encouraged by the recent inauguration of the Suez Canal - decided to invest in the Corinth Canal. But financing problems delayed the start of construction until 1882 and it took 11 years to complete.

From its beginnings, the Corinth Canal was born with problems that have hindered the exploitation of its potential. It is a very narrow seaway - it is only 21 meters wide - and has a shallow draft (8 meters deep), which is why larger vessels prefer to avoid it.

The Kiel Canal and the naval ambitions of the Kaiser

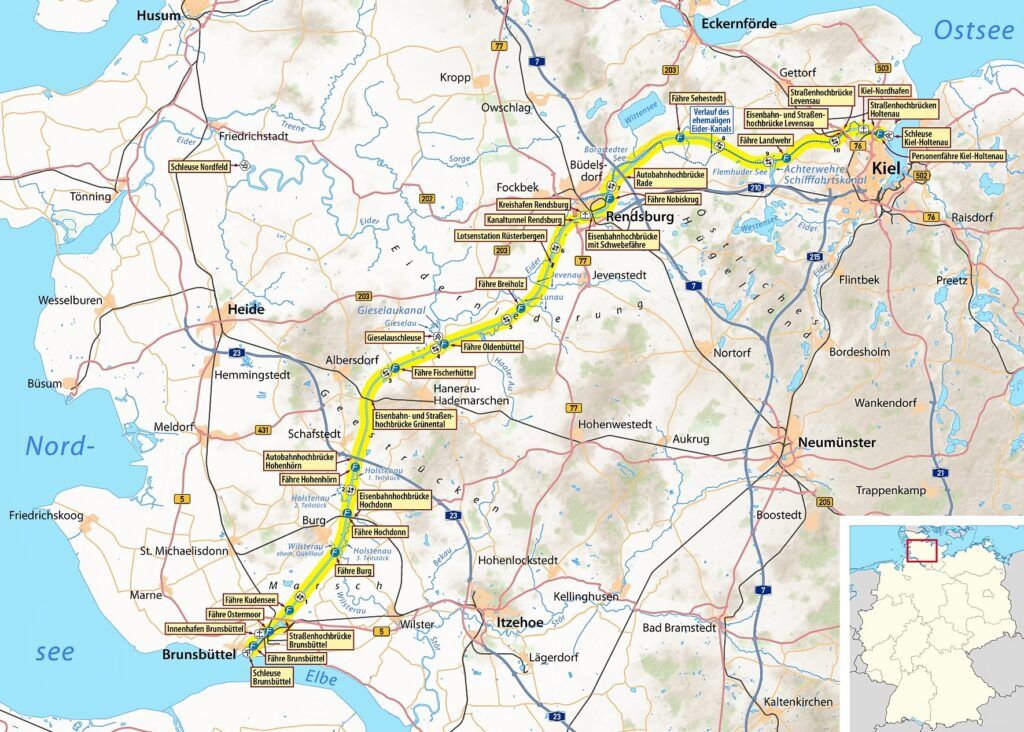

Without having to go back to antiquity, another project to highlight and which has worked better is the Kiel Canal, which connects the North Sea with the Baltic, thus avoiding the need to go around the Jutland peninsula (Denmark).

The predecessor of the Kiel Canal was the Eider Canal, built between 1777 and 1784 by order of Duke Adolf of Holstein-Gottorp, third son of King Christian III of Denmark. The route stretched 173 kilometers and required the installation of six locks to overcome the orographic gradients.

The Eider Canal can be considered to have died of success. It soon took on a very high volume of maritime traffic. In addition, the increase in the displacement and draft of ships in the 19th century pushed its capacity to the limit. These technical issues combined with the geopolitics of the time conditioned its future.

Prussia annexed the territories where the Eider Canal was located in the war of 1866 and Berlin explored in the following years the improvement of the infrastructure. The strength of Kaiser Wilhelm II's merchant fleet and navy made it necessary to improve the infrastructure, and between 1887 and 1895 the Kiel Canal was built, connecting this Baltic port with Brunsbüttel on the North Sea. Germany's maritime strength in the early years of the 20th century led to periodic extensions until 1914.

Canals in the heart of Europe: past... and future

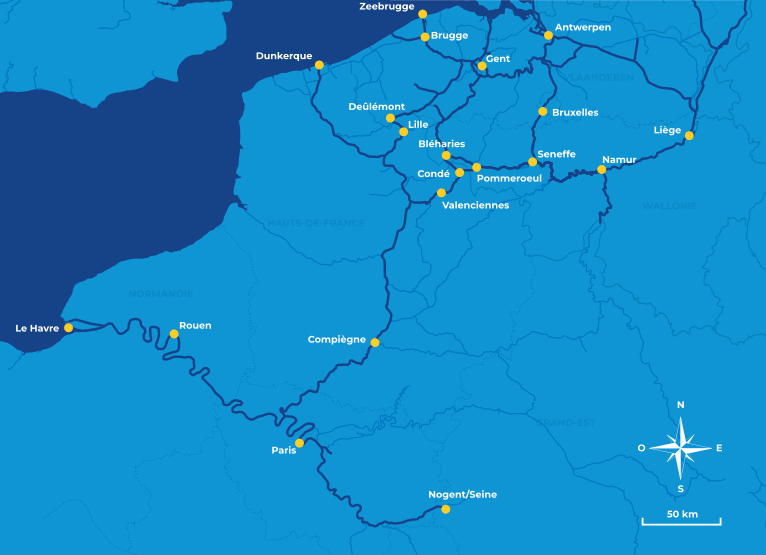

This type of infrastructure in the heart of Europe is nothing new, however. A forward-looking initiative promoted by the EU to improve connections in the Scheldt and Seine basin, as well as those of the Rhine and the Maas, stands out.

Both projects, with an investment of 300 million from the CEF (Connecting Europe Facility), aim to create cross-border waterways of some 1,100 kilometers. The Seine-Escalade will be operational in 2030 thanks to an extensive program of works initiated in France and Belgium to regenerate, extend and modernize existing waterways that will be connected to the Seine-Northern Europe Canal.

The construction of a new river infrastructure, the Seine-Northern Europe Canal, which will connect the Seine and Scheldt basins, as well as other major European basins (Meuse, Rhine), will also help.

The Seine-Scheldt network will run through a territory that includes several large cities where 40 million people live and work, and will open a new gateway to Europe for trade in goods and passenger transport.

The project will create a new transport offer for Europe that is multimodal, cross-border, coherent, interconnected, comprehensive, accessible, modern, safe, clean and efficient, accelerating modal shift to inland waterways.

The Suez Canal, the eternal competition between powers

The recent geopolitical tensions surrounding the Suez Canal and the Panama Canal are nothing new from a historical point of view. The reduction of traffic on the Egyptian waterway due to the Houthi attacks, as well as the drought and Trump's statements are just new episodes in a long history of geopolitical pugnacity in both infrastructures.

In fact, the interplay of interests between powers marked the birth of the project, it should not be forgotten that they were born in the last decades of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, a time of competition between great powers.

The Suez Canal project was launched with the open opposition of the great power of the time: Great Britain. Lord Parlmeston led this position when he was Prime Minister between 1859 and 1865. London took a dim view of losing its monopoly of maritime communication across the Cape of Good Hope and feared that its connections with India could be threatened.

Little by little the British position changed. Particularly when the Suez Canal became operational in 1869 and they saw that they were more interested in controlling it because of the possibilities it offered to improve trade connections with their great empire (and especially with India, the Jewel of the Crown).

Britain took advantage of the financial problems of Ismail Pacha, Egypt's khedive, to buy 44% of the shares of the company that managed Suez. In addition, Her Majesty's government warned rival powers (particularly Russia and France) not to interfere in the security of Suez.

The final blow of the British came in 1882. With the excuse of protecting European citizens in the face of a nationalist revolt, London sent its troops and turned the Arab country into a de facto protectorate and controlled Suez. A dominion that the rest of the powers would recognize in 1888 in the Convention of Constantinople and France accepted to play a secondary role.

Egypt had to recognize British rule, which would be ratified by the 1936 treaty. But on July 26, 1956, the government of Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the Canal. Great Britain, allied with France and Israel, tried to regain control, giving rise to the Suez crisis, which was the swan song of the colonial ambitions of London and Paris over this infrastructure.

In the following decades, geopolitical disputes in Suez were marked by the Arab-Israeli conflict. The Canal was closed between 1967 as a consequence of the Six Day and Yom Kippur wars, as both banks of the Suez were the front line between Egyptian and Hebrew troops. Much of the oil going to Europe had to be diverted through the Cape of Good Hope.

The Panama Canal, a history of tensions

The Panama Canal was also born in a climate of disputes between powers. In the mid-19th century, the British and Americans were vying to lead the project linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. London was thinking more of a project across Lake Nicaragua, while Washington had already set its sights on the Panamanian isthmus (then under Colombian sovereignty).

The project defended by the British through Lake Nicaragua is reminiscent of the option that began to be promoted in 2012 by Chinese initiative and in agreement with the government of Beijing. At the end of the last decade it seemed to have been abandoned but, as a result of the drought problems and with Trump's declarations, it has been recovered by Daniel Ortega's executive.

Over the following decades, the US and Colombia negotiated the development of the project, but the idea aroused much opposition in the Latin American country for fear of US intentions. For its part, Washington wanted to build the Canal as soon as possible to facilitate the development of the states on its Pacific coast.

In the end, under another president with imperial aspirations such as Theodore Roosevelt, the US supported the independence of Panama in 1903, intimidating Colombia militarily. On November 6 of that year, the agreement was signed that gave the Americans the rights to build the Canal, works that would be completed in 1914.

After World War II, the US anti-colonial discourse that had forced Britain and France to back down in the Suez Crisis generated pressure on Washington to seek an agreement to cede control of the Canal to Panama. In this context, the Torrijos-Carter agreement was signed in 1977, setting an end date for US control: December 31, 1999.

Even after the signing of the agreement, and before Trump's statements, the United States has always been energetic when it comes to defending its interests in the Panama Canal, as demonstrated with the invasion of the Central American country in 1989 to depose dictator Manuel Noriega, a former ally turned rival.

In these first days of Trump's mandate, the US is pressing for its ships, not just those of the navy, to have free passage through the intra-oceanic canal, in fact the White House announced it, but this supposed agreement has been denied by both the government of Panama and the authority that manages the canal.

New sea routes, new projects, old needs

Today's world is drawing a new panorama of relations between great powers that will influence the development of new infrastructure and maritime routes.

The routes in the Arctic and through the Northwest Passage seem to be the next to gain prominence, without forgetting the improvement of the capacities of the already existing canal systems. Or projects that remain, for the moment, very theoretical: such as the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, which would connect the port of Coatzacoalcos (Gulf of Mexico) with Salina Cruz (Pacific). It is a project of the Mexican government that would involve an estimated investment of 1,000 million and would seek to reduce transit time by 5-6 days compared to the Panama Canal. Along the same lines, there is also talk of the Colombian Dry Canal, which would connect the Gulf of Urabá (Atlantic) with Bahía Cupica (Pacific).

Geography and commerce forcing us to think about new routes, since the dawn of time.