The economy of the sea emerged about 15 years ago and it originated in the integrated maritime policy of the European Union. (GettyImages)

The economy of the sea emerged about 15 years ago and it originated in the integrated maritime policy of the European Union. (GettyImages)

Blue economy: this is how cities and ports collaborate towards sustainable growth

The sea is and has been a great source of wealth and supply for a multitude of industries. However, it is also a fragile, degraded and exploited ecosystem. Ensuring its good health requires executing actions that enhance biodiversity through technology, investment and the development of social, environmental and economic strategies. This is what the so-called "blue economy" seeks and involves broad verticals and an opportunity for the sustainable growth of cities and ports. This is perceived in the Port of Vigo, which has become a European benchmark, and in Barcelona, where the city council and the Port have signed an agreement to create a blue economy hub.

The economy of the sea emerged about 15 years ago and it originated in the integrated maritime policy of the European Union. (GettyImages)

The economy of the sea emerged about 15 years ago and it originated in the integrated maritime policy of the European Union. (GettyImages)

What is the blue economy?

Although its origin is earlier, the concept of the blue economy was officially coined at the Rio + 20 Conference organized by the United Nations in 2012 under the premise that “healthy ocean ecosystems are more productive and represent the only way to guarantee that the economies that depend on the sea are sustainable.”

“The economy of the sea emerged approximately 15 years ago and has its origins in the European Union’s integrated maritime policy. That's when awareness that the sea has autonomous industries with its own identity was raised. Now, it emphasizes their added value, in which the key word is 'integrated',” explains Miguel Marques, international consultant in Blue Economy.

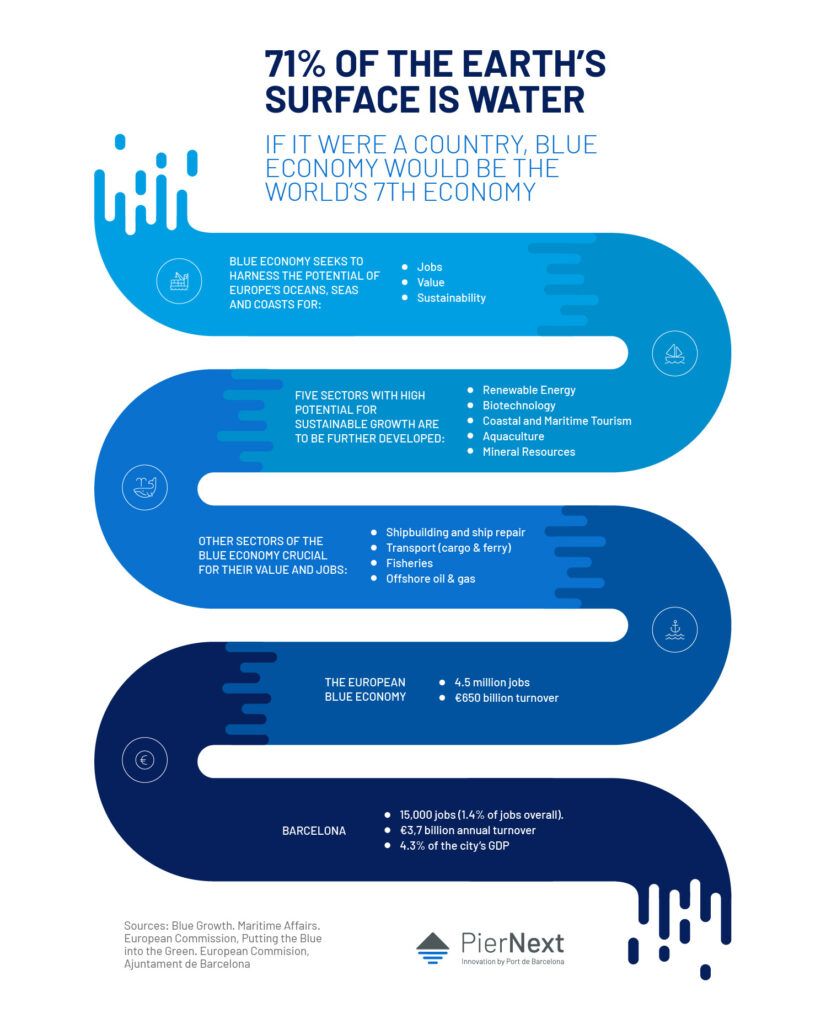

If the global blue economy were a country, it would be the seventh largest economy in the world. It is an economic segment that includes sectors such as fishing, aquaculture, maritime transport, marine biotechnology, tourism, renewable energy and mining, among others.

Innovation, technologies and investments at the heart of marine sustainability

An essential part of the blue economy lies in putting cutting-edge technologies and public and private investments at the heart of its development. Both are brought together by Seastainable Ventures, a venture building platform that connects and catalyzes investments in innovative projects from the environment of the sustainable marine economy, mainly in the Mediterranean Sea. As its founder and president, Ignasi Ferrer, explains: “We have developed a network of 190 international scientific entities that work on the restoration, enhancement and management of marine natural capital. Through them we identify knowledge and technologies and help us evaluate possible opportunities. In addition, we have more than 70 international start-ups on our radar that work in the environment of the blue economy, which we help to grow and promote their projects.”

For Ferrer, attracting investment is essential to solve many problems the marine environment faces, mainly related to the loss of biodiversity. For this reason, he adds, the criteria for investment on the blue economy is not all about profitability; it also seeks to contribute to attract resources that strengthen sea recovery or offset human activity by generating a net zero emission effect.

He also highlights several innovations in fields such as regenerative tourism and biotechnology, such as the Barcelona-based Ocean Ecostructures, which regenerates marine structures such as wind turbines, oil rigs or degraded docks by installing calcium carbonate structures that blend in with nature and allow fish and algae to approach these pieces forming reefs of marine life.

If the global blue economy were a country, it would be the seventh largest economy in the world

Cities and ports, a key alliance for the blue economy

Several cities are positioning themselves to become the epicenter of the blue economy with an essential ally: ports. The City Council and the Port of Barcelona, for example, have signed a collaboration agreement to develop a blue economy hub that covers the entire Barcelona coastline. The sectors associated with the blue economy currently generate 15,000 jobs (1.4% of the whole employment), 3.75 billion euros in annual turnover and represent 4.3% of its GDP.

“Barcelona has an excellent foundation due to its location. Its port is a benchmark in the Mediterranean sea and its scientific and entrepreneurial fabric are central to generating knowledge. If you add all these factors to a maritime industry already consolidated from the Port, there are opportunities for the city to establish its leadership on the blue economy,” says Ferrer.

For Marques, "the role of ports continues to evolve. Now they have the opportunity to become the physical interface where all the blue economy verticals can converge." His statement is in line with the European Commission’s statement on a new approach for a sustainable blue economy in the EU, published in May, which highlights that “beyond tranport and logistics, their future lies in developing their key role as energy hubs (for integrated electricity, hydrogen 12 and other renewable and low-carbon fuels systems), for the circular economy, for communication, and for industry.”

Blue Growth Vigo project, pioneer in Europe

European cities such as Genoa and Lisbon are also moving to take advantage of the growth opportunities the blue economy offers. In Spain, the Vigo Port Authority established the Blue Growth Vigo strategy, divided into two stages; 2016-2020 and 2021-2017, to channel initiatives framed within the sustainable marine economy.

Vigo's action plan is based on integrating the port and the companies and groups that operate in the port area with the city to generate a positive impact on the economy, employment and well-being of people and the environment.

Its added value, according to Carlos Botana, Head of the Sustainability Department of the Vigo Port Authority are the added factors that characterize the environment of Vigo and the municipalities of its estuary, which have traditionally lived from the exploitation of marine-coastal resources through the tourism, fishing, maritime transport and shellfish. The area also has, among others, a natural capital of high biological and landscape value and is strategically located in the Atlantic Corridor.

“All this allows us to have a high level of concentration of knowledge centers, represented by the Campus do Mar and research and technology centers, business organizations from the marine-coastal economic sectors, administrations with experience in territorial development and a civil society sensitized and involved in these challenges. This involvement and public-private cooperation are the key to success,” he says.

In the first stage, 38 projects were carried out and 44 actions were proposed. For the second, they have been expanded to 46, 25 of which are in execution. Initially, 14 working groups were established - one per key area - now reduced to 6.

“We knew that only if we were able to work with the same intensity in each of these key areas would we be able to generate a positive impact. On the other hand, we would like to highlight the impact indicators used to measure these strategies, based both on the performance of the plan itself and on its ability to generate change,” he explains.

Botana shares a final thought on the role of ports in the context of the blue economy: "From the design of the plan, we knew that no port can be successful if it works in isolation." Vigo currently holds the presidency of the Blue Growth Group of the European Organization of Maritime Ports (ESPO) and is the recipient of the sustainability award granted by the International Association of Ports (IAPH) for the “Peiraos do Solpor” project, whose objective is to transform “gray” or degraded infrastructures of the port environment into green infrastructures.

Components of the Blue Economy

| Type of Activity | Activity Subcategories | Related Industries/Sectors | Drivers of Growth |

| Harvesting and trade of marine living resources | Seafood harvesting | Fisheries (primary fish production) | Demand for food and nutrition |

| Seafood harvesting Fisheries (primary fish production) Demand for food and nutrition Secondary fisheries and related activities (e.g., processing, net and gear making, ice production and supply, boat construction and maintenance, manufacturing of fish- processing equipment, packaging, marketing and distribution) | Demand for food and nutrition | ||

| Trade of seafood products | Demand for food, nutrition | ||

| Trade of non-edible seafood products | Demand for cosmetic, pet, and pharmaceutical products | ||

| Aquaculture | Demand for food, nutrition | ||

| Usage of marine living resources for pharmaceuticals and chemicals | Marine biotechnology and bioprospecting | R&D and usage for health care, cosmetic, enzyme, nutraceutical, and other industries | |

| Extraction and use of marine nonliving resources (non-renewable) | Extraction of minerals | (Seabed) mining | Demand for minerals |

| Extraction of energy sources | Oil and gas | Demand for (alternative) energy sources | |

| Freshwater generation | Desalination | Demand for freshwater | |

| Use of renewable non-exhaustible natural forces (wind, wave, and tidal energy) | Generation of (offshore) renewable energy | Renewables | Demand for (alternative) energy sources |

| Commerce and trade in and around the oceans | Transport and trade | Shipping and shipbuilding | |

| Maritime transport | Growth in seaborne trade; transport demand; international regulations; maritime transport industries (shipbuilding, scrapping, registration, seafaring, port operations, etc.) | ||

| Ports and related services | |||

| Coastal development | National planning ministries and departments, private sector | Coastal urbanization, national regulations | |

| Tourism and recreation | National tourism authorities, private sector, other relevant sectors | Global growth of tourism | |

| Indirect contribution to economic activities and environments | Carbon sequestration | Blue carbon | Climate mitigation |

| Coastal Protection | Habitat protection, restoration | Resilient growth | |

| Waste Disposal for land-based industry | Assimilation of nutrients, solid waste | Wastewater Management | |

| Existence of biodiversity | Protection of species, habitats | Conservation |